Did former president Jerry Rawlings really beat up his veep in a political feud?

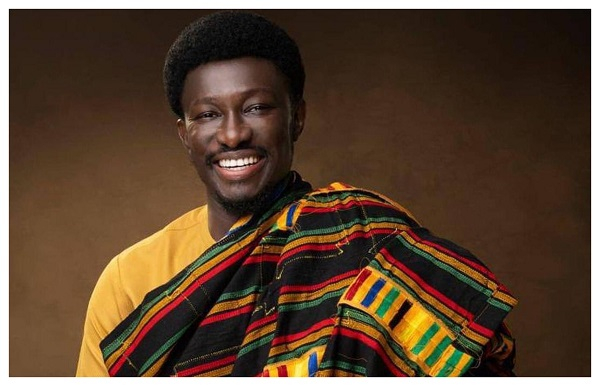

Very few living statesmen on the African continent possess the myth-cum-fact biography of Ghana‘s former President Jerry John Rawlings, the country’s longest-serving head of state.

For starters, Rawlings, by virtue of his initials J.J. was called Junior Jesus by the commonfolk from about 1979. He was the savior who was going to give back to the people what the ruling elite have stolen.

One of the most creative ways through which Rawlings endeared himself with Ghanaians was an effortless campaign to identify with the people’s problems. This campaign was one part self-denigration and another part self-promotion.

For instance, Rawlings is known to have spoken about how he was constantly forced to buy beans and gari, a Ghanaian staple food, on nothing but his good word to pay later. The point here was that he grew up poor, just like the thousands who thronged to his rallies in the 1980s and they did not mind that sometimes, he would not even pay for the beans and gari.

The people laughed about Rawlings absconding with his debts because sometimes, they too were also never in the place to pay theirs.

But did Rawlings really grow up struggling? Well, the man himself has not been generous with information that lends credence to the grass-to-grace perspective with which all of Ghana looks at him.

Born in 1947, Rawlings is the lovechild of a Ghanaian woman, a hotel aide at the time, and a married Scottish pharmacist who was working in pre-independent Ghana. Not much is even known about the families his mother and father raised apart.

But the man who was clearly Ghana’s most popular leader only second to Kwame Nkrumah attended Achimota School, incidentally a school that also counts Nkrumah as an alumnus. Established in 1927 by colonial administrators, Achimota School became a first-class institution available to intelligent, mostly, young boys of the Gold Coast or those with parents who could afford Achimota.

Whatever Rawlings’ association with Achimota School tells us about the kind of circumstances in which he grew, he graduated in 1968 and went straight into the Ghana Air Force.

Rawlings, a despot turned democrat

Rawlings was admired for his good looks, boyish exuberance and military-inculcated authoritarianism. But he also spoke of values that carried his charisma – in his words, “probity and accountability”. As a military ruler, he vowed to make those who had plundered and looted and “bled Ghana to the bone” pay for their transgressions.

In his first coup in 1979, he did “let the blood flow”.

In his second coup in 1981, he was going to “organize this country in such a way that nothing will be done, whether by God or the devil, without the consent and the authority of the people.”

The topic of how to look at Rawlings’ military rule will probably require a longer piece than this one. All may, however, agree on one thing – he was a man to whom Ghanaians gave a considerable amount of chances.

After Ghana returned to multiparty democracy in 1992 under his stewardship, Rawlings and his National Democratic Congress (NDC) won the presidency and the legislature.

This pointed to the fact the people were at least, willing to overlook all of Rawlings’ own transgressions which included the collapse of thousands of business ventures belonging to individuals, acquiescing to World Bank-suggested policies of privatizing now-defunct government-owned factories, extrajudicial killings and fostering a culture of silence.

We may also theorize that Rawlings’ victory was also aided by his choice of running-mate, Kow Nkensen Arkaah, a wily veteran of Ghanaian politics.

Arkaah was the leader of the National Convention Party (NCP), a party that claimed Nkrumahism, the values of Ghana’s first president, as its principles. Rawlings’ NDC, however, went into alliance with the NCP.

The choice of Arkaah gave an aura of respectability to Rawlings’ candidacy. Arkaah was an MBA-wielding marketing executive who was 20 years older than Rawlings and came from a noble family in Western Ghana – he could complement the young man’s inexperience and even, tame a wild soldier.

But the hell to which these good intentions paved began somewhere in 1995, about 18 months to the 1996 general elections. The two had a public fallout and Arkaah pulled his party from the alliance but refused to resign as vice-president of Ghana.

Arkaah also stated that his intention was to marry the NCP with the New Patriotic Party (NPP), the biggest opposition party come the 1996 election.

These were tense times in Ghana’s democratic infancy and there were some in the country who feared that Rawlings might not wait for the next ballots before resorting to bullets. This was rational fear, if there is any such thing.

Did Rawlings slap Arkaah?

According to former First Lady Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings, a decision to keep Arkaah out of cabinet meetings was taken by ministers who then informed President Rawlings. The vice-president had become not only persona non grata but a known enemy within.

On December 28, 1995, there was a cabinet meeting that Arkaah attended, according to Agyeman-Rawlings. She was not at the meeting but she told the story in 2013 about what her husband and another person at the meeting had confided in her:

“But Vice-President Arkaah walked in and nobody was able to tell him to leave. At that time, my husband wasn’t in…he walked in later…He [Rawlings] then went to him [Arkaah] and said “I think you should leave”. He [Rawlings] put his hand on his [Arkaah] shoulder…and the guy kind of struggled and tumbled off his chair.”

Whatever impression the former first lady picked up was totally different from what the world heard from Arkaah on December 29, 1995. At a press conference in Accra, Arkaah said the NDC government had “become the forum for corrupt and unscrupulous plans” while showing a suit ripped at the shoulder and explicitly stated that he was assaulted by the president.

“At 10:30 am, the President, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings entered the room…He began to make a statement on the recently held congress of my Party, the National Convention Party, but stopped short midway and without any provocation, physically assaulted me,” said Arkaah.

Government communication the night before had said that Arkaah was gently asked to leave the meeting because of negative remarks he had made regarding the cabinet.

But the then 68-year-old Arkaah had a vastly different recollection of matters:

“[Rawlings] gave me a terrible blow on the shoulder which sent me falling to the floor. He then attempted to pull me up by the shoulder in order to hit me further; he tore the shoulder of the jacket in the process. In his frustration, he kicked me a couple of times in the groin, before members present were able to restrain him.”

Arkaah continued that he had wanted to stand his ground against the 48-year-old burly soldier who stands about six feet but “with pleadings from colleagues”, he decided he had to leave.

Writing in 1996 on how the two versions of the incident were received, Frank Agyekum (who became a spokesperson to future Ghana president John Kufour), argued that “[P]ublic sympathy on the incident is divided.”

But this may have been an overly-diplomatic summation of public opinion because 25 years on, one is more likely to find in Ghana believers of Arkaah’s version of the story than the Rawlings’. It is also not hard to see why this is the case.

Arkaah, who died in 2001 in the United States, was a diminutive man and physically frail in 1995. And Rawlings has all the political history of a man we will find difficult to defend as “[incapable] of beating anyone” like Agyeman-Rawlings said.

But of course, who stood at what height and who looks like they can be violent are purely circumstantial reasons to believe either side. The ministers in that room that morning are also obvious biased reporters of the incident.

Source: face2faceafrica.com