Covid: South Africa halts AstraZeneca vaccine rollout over new variant

South Africa has put its rollout of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine on hold after a study showed “disappointing” results against its new Covid variant.

Scientists say the variant accounts for 90% of new Covid cases in South Africa.

The trial, involving some 2,000 people, found that the vaccine offered “minimal protection” against mild and moderate cases.

But experts are hopeful that the vaccine will still be effective at preventing severe cases.

South Africa has recorded almost 1.5 million coronavirus cases and more than 46,000 deaths since the pandemic began – a higher toll than any other country on the continent.

The country has received one million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab and was preparing to start vaccinating people.

On Monday, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned against jumping to conclusions about the efficacy of Covid vaccines.

Dr Katherine O’Brien, the WHO’s director of immunisation, said it was very plausible that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine would still have a meaningful impact on the South African variant, especially when it came to preventing hospitalisations and death.

“Comparing from one piece of evidence to the next really can’t be done without a sort of level playing field,” she said, referring to the evaluation of different trials in different populations and age groups.

Dr O’Brien stressed that the WHO’s expert panel held “a very positive view” of proceeding with the use of the vaccine, including in areas where variants were circulating, but that more data and information would be needed as the pandemic continued.

South Africa’s Health Minister Zweli Mkhize said his government would wait for further advice on how best to proceed with the AstraZeneca vaccine in light of the findings.

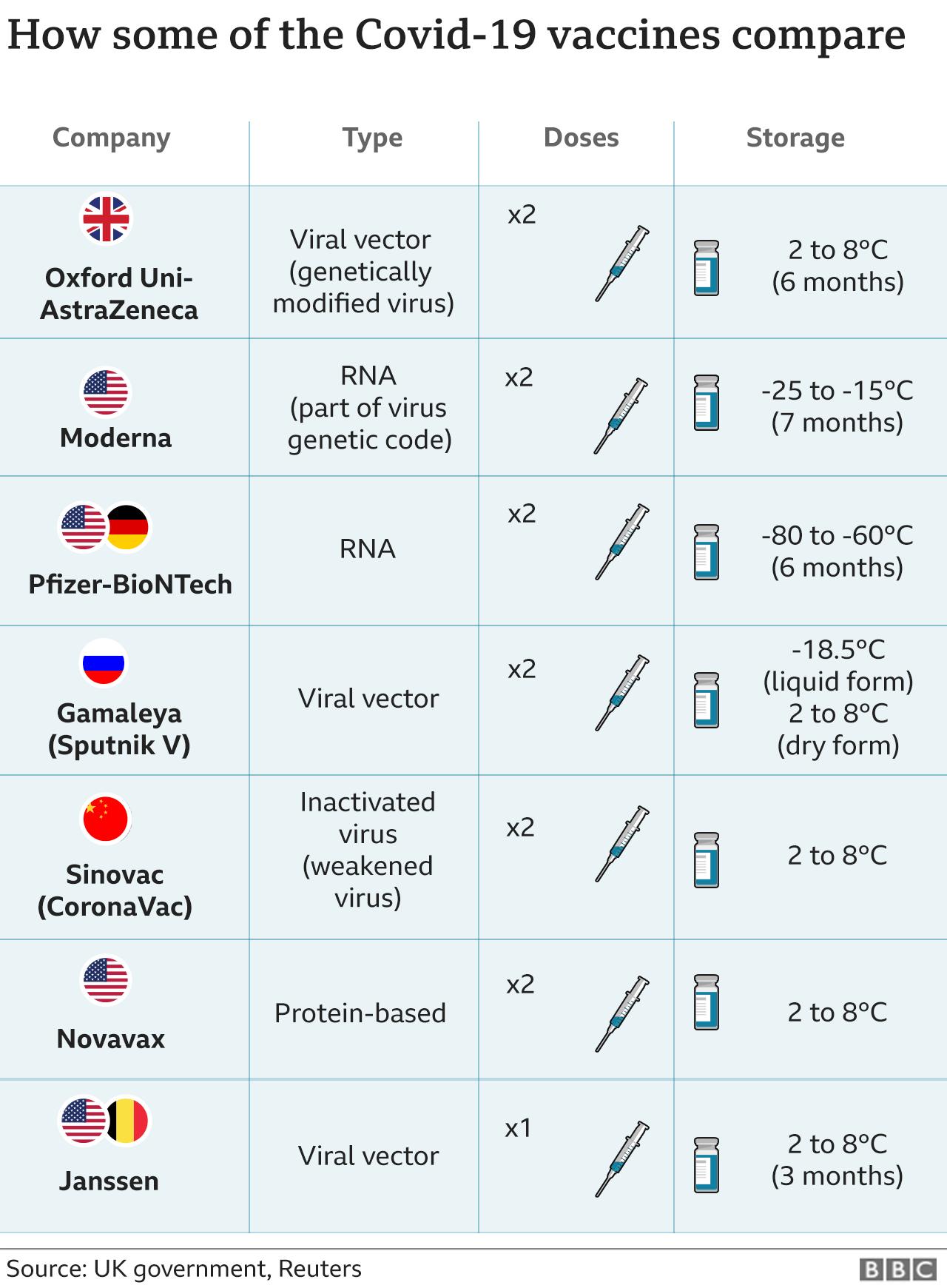

In the meantime, he said, the government would offer vaccines produced by Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer in the coming weeks.

What does it mean for serious cases?

The trial was carried out by researchers at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa and the UK’s Oxford University, but has not yet been peer reviewed.

The trial’s chief investigator, Prof Shabir Madhi, said it showed that “unfortunately, the AstraZeneca vaccine does not work against mild and moderate illness”.

Prof Madhi said the study had not been able to investigate the vaccine’s efficacy in preventing more serious infections, as participants had an average age of 31 and so did not represent the demographic most at risk of severe symptoms from the virus.

The vaccine’s similarity to one produced by Johnson & Johnson, which was found in a recent study to be highly effective at preventing severe disease in South Africa, suggested it would still prevent serious illness, according to Prof Madhi.

“There’s still some hope that the AstraZeneca vaccine might well perform as well as the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in a different age group demographic that I address of severe disease,” he told the BBC.

Other experts were also hopeful that the vaccine remained effective at combating more serious cases.

“What we’re seeing from other vaccine developers is that they have a reduction in efficacy against some of the variant viruses and what that is looking like is that we may not be reducing the total number of cases, but there’s still protection in that case against deaths, hospitalisations and severe disease,” Prof Sarah Gilbert, Oxford’s lead vaccine developer, told the Andrew Marr Show on Sunday.

She said developers were likely to have a modified version of the injection against the South Africa variant, also known as 501.V2 or B.1.351, later this year.

Ministers in the UK have sought to reassure the public over the effectiveness of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. Vaccines Minister Nadhim Zahawi said the injection appeared to work well against dominant variants in the UK, while Health Minister Edward Argar said there was “no evidence” the vaccine was not effective at preventing severe illness.

Early results from Moderna suggest its vaccine is still effective against the South Africa variant, while AstraZeneca has said its vaccine provides good protection against the UK variant first identified late last year.

Early results also suggest the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine protects against the new variants.

We should be careful about rushing to judgement

Viruses mutate – so what is happening is not surprising.

The mutations seen in South Africa change the part of the virus that the vaccines target. It means all the vaccines that have been produced so far are likely to be affected in some way.

Trials for Novavax and Janssen vaccines that were carried out in South Africa showed less effectiveness against this variant. Both are currently before the UK regulator.

Therefore the news about Oxford-AstraZeneca does not come out of the blue.

The fact it now only has “minimal” effect according to reports is concerning – the other vaccines showed effectiveness in the region of 60% against the South African variant.

But we should be careful about rushing to judgement. The study was small so there is only limited confidence in the findings.

What is more, there is still hope the vaccine will prevent serious illness and hospitalisation.

What this once again illustrates is the pandemic is not going to end with one Big Bang. Vaccines are likely to have to change to keep pace with the virus.

Progress will be incremental. But vaccines are still the way out of this.

What do we know about the variant?

The South Africa variant carries a mutation that appears to make it more contagious or easy to spread.

However, there is no evidence that it causes more serious illness for the vast majority of people who become infected. As with the original version, the risk is highest for people who are elderly or have significant underlying health conditions.

At least 20 other countries including Austria, Norway and Japan, have found cases of the variant.

Health officials say all is not lost

Many South Africans have reacted with shock and disappointment at news that the 1.5 million doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines will not be as effective as experts had hoped against the new variant first discovered here in November.

While there are now more questions than ready answers, the message from health officials is that all is not lost. They believe the vaccine may still be effective in preventing severe illness and go some way in reducing the number of people who need to be admitted into hospital for treatment.

This is important in a country where some 80% of the population cannot afford private health care and rely on state hospitals – which are currently overstretched – for health care.

So what’s the plan now? South Africa’s health minister has said they will take a steer from local scientists on how to repurpose the vaccine to get the most out of it.

It has been suggested that the vaccine may be useful if given to the older population and to people with co-morbidities.

In terms of managing people’s concerns, the government and scientists may need to go the extra mile in reassuring citizens that there is still a plan in place and lives can and will be saved.