Covid in Uganda: The man whose children may never return to school

Ten of Fred Ssegawa’s children may never go back to school again.

Locked out of formal education since March 2020 by Uganda’s strict coronavirus containment measures, they have been caught up in one of the world’s longest school shutdowns.

The two youngest of his 12 children were too little to have started in the first place.

Mr Ssegawa – a teacher of 20 years – has been shorn of his small income of around $40 (£30) a month.

When he had a job he struggled to keep the children in school. Now that the 49-year-old has taken to full-time farming he has turned his back on teaching. He wants to develop the small amount of land he has.

He gets three of his children, aged between 10 and 15, to work alongside him. The older ones scrape together money however they can.

President Yoweri Museveni has insisted that the continued school closure was essential to keep people safe until enough adults are vaccinated.

It is true that cases and deaths from coronavirus have been relatively low, but the experiences of Mr Ssegawa and his family show the broader impact that the health measures have had.

I found him, two of his daughters and a son, picking the season’s harvest of beans at their farm in Luweero, about a three-hour drive north of the capital, Kampala.

Beads of sweat form on their foreheads as they bend and rise, plucking and gathering the bean stalks in bundles.

The beans are planted alongside maize and cassava – sustenance for the family of 14.

“Some [of my children] were in boarding schools. They had not done this farming work before. But with this situation, they have been forced to learn,” Mr Ssegawa says, as the young ones rummage through weeds, picking the beans.

Two of his older children, both boys, had been preparing for crucial exams when the schools closed. Only one was able to return when they temporarily reopened in October 2020 for pupils to sit the tests.

‘I’d rather be in class’

That was Daniel, 21, who had planned to go to university.

Instead he now makes bricks for sale on the edge of the family land, chipping away at a huge anthill, mixing the mud, and compacting it.

He and a cousin are covered from head to toe in golden-brown mud.

Although his dreams of further education are now dashed, by selling each brick at 80 Uganda shillings ($0.02), Daniel hopes to support his younger siblings to get a few more years of schooling.

But for the moment, his 16-year-old brother Paul spends his time chopping up tomatoes and onions at a small thatched stall a few minutes’ walk from their home. He makes chapati and omelette snacks, known here as “rolex”, for sale.

“The pandemic affected my studies. I had to work and pay my own school fees. I don’t like this work. I would rather be in class,” he says, adding that he does not think he can earn enough to go back when the schools re-open.

Although there are no fees in Uganda’s public schools, parents are still expected to pay for the uniform and some basic materials, which are beyond the reach of some. Also, in many rural areas, there are simply not enough teachers and classrooms to absorb all the potential students.

Mr Ssegawa says it hurts him to watch his children struggle.

“I had wanted all my children to complete secondary school, at least. But I don’t think that will be possible.

“I know the value of education. These days, you cannot get decent work without a qualification. It makes me sad, seeing my children like this,” says the former social studies and science teacher.

There have been some lessons on the radio and TV, and newspapers and some schools have provided printed materials, but these have not reached everyone.

A study in April by the Forum for African Women Educationalists found that for just over half of the country’s 15 million school pupils, education had stopped entirely, with primary school children the worst hit.

Wealthier Ugandans have been able to access online classes and home tutors, but not Mr Ssegawa.

“I heard on the radio that there were study materials the government was making for learners. But we didn’t get them,” he says.

‘My life changed when I got pregnant’

His niece, 17-year-old Madina Nalutaaya, lives a 30-minute drive from the Ssegawas’ village.

She too will not be returning to school.

She was in the penultimate year of primary school before the lockdown. Now she is the mother of a two-month-old baby girl.

Her current situation seems overwhelming and getting her to open up proves quite difficult.

Looking down at the baby in her arms, she speaks in clipped sentences.

“My life changed when I got pregnant. My child’s father ran away.”

Uganda’s National Planning Authority estimated in August that 30% of all the country’s learners would not be going back to school due to teenage pregnancies, early marriages, and child labour.

The government’s health data show that cases of pregnancy among girls aged 10-14 more than quadrupled between March, when the schools were first closed, and September 2020.

The Ugandan education system allows young mothers to return to school, but many lack a support system at home or means to provide for their babies.

“I have someone I could leave my baby with, but I would not be able to raise my school fees, and money for my child’s needs,” says Madina.

The government has pegged the planned January re-opening of schools on the vaccination of students aged 18 and over, as well as all teachers.

But the authorities may be faced with a problem.

There are some teachers, like Mr Ssegawa, who took to farming or other found better-paid work to provide for their families, and are unlikely to return to the classroom.

Mr Ssegawa himself sees no future in teaching and hopes that one day his farm could make him some money.

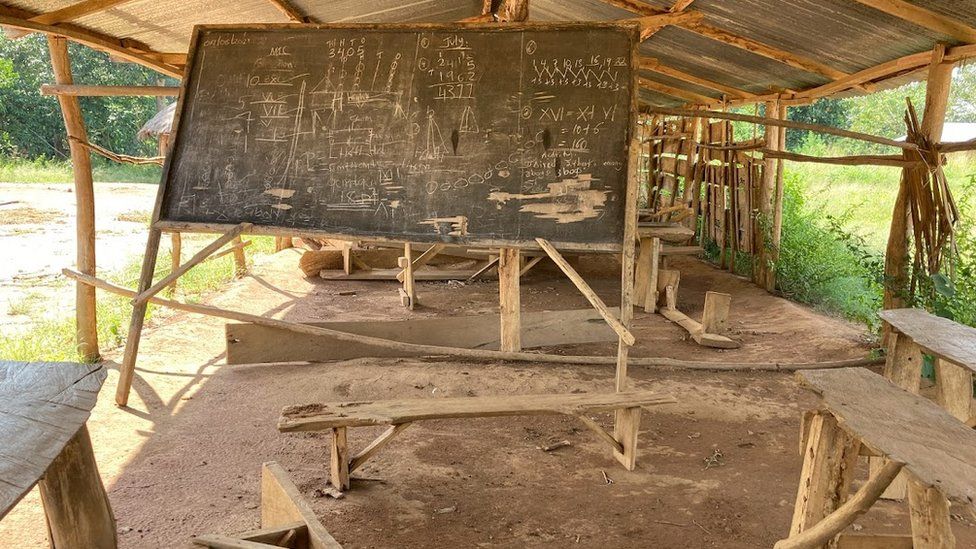

School buildings have become run down and some 4,300 schools could remain closed because of financial problems, according to the National Planning Authority.

The children will also be a long way behind where they are expected to be.

Officials are recommending that the school week be extended and the holidays shorter to help make up for lost time.

Primary Education Minister Joyce Moriku Kaducu has said her ministry is recruiting more teachers and funding the refurbishment of schools.

“The curriculum has been revised too, in such a way that we get the critical content… so that [the pupils] complete the education cycle within that designated period,” she adds.

Impact of less education

There are also plans to target children who are at high risk of dropping out or offer technical and vocational training as an alternative.

But there are the long-term consequences to contend with.

Dr Ibrahim Kasirye, research director at Makerere University’s Economic Policy Research Centre, says that a poorer education reduces the chances of finding decent, well-paid work, making it harder to escape poverty.

“This could lead to an increase in youth crime, because these young people must find a way to survive,” he told the BBC.

Back on Mr Ssegawa’s farm, he is feeling hopeless.

Resting in the shade with his children after a day’s harvesting he says his heart breaks for them when he thinks about their future.

He pins their chances on an expansion of the free primary school education programme in the rural areas, but that may not happen soon enough.

BBC.COM