BETWEEN MEMORIES AND FORGETFULNESS: A Focus on Monuments in Kumasi

Kumasi is replete with powerful history and rich culture. Some aspects of Kumasi’s history are embedded in monuments speaking volumes. Monuments in public spaces don’t just emerge out of thin air. In the strictest sense, monuments are the products of collective human efforts — often expensive and time-consuming — erected to commemorate or honor a person or a historical event. As statements of power, monuments such as the colossal statues of Kim Il Sung, Stalin and Lenin have throughout recorded history, been towering reminders of the central government’s unquestionable authority in communist regimes.

Almost all roundabouts in Kumasi boast of historical monuments. They are predominantly Kings and Queens who ruled Asante Kingdom; heroes who sacrificed their lives for the betterment of the Kingdom; and totems revered as a symbol of a clan. There was one time a monument of the sacred Golden Stool at the old Kejetia Market Roundabout. Some of the popular monuments in Kumasi now are Okomfo Anokye at “Gee” Roundabout, a man in a traditional cloth at Prison’s Roundabout, Otumfuo Opoku Ware II at Suame Roundabout, among others.

According to Mr. James Boakye, a skilled private sculptor at the Centre for National Culture, Kumasi, these monuments take us through mental excursion or exploration of knowing our past and connecting it with the future. It is to make it easy for people from all walks of life to remember our forebears, be familiar with their history and achievements as well.

These historical statues give glorified pictures of the city. I was young when the statue of the late Otumfuo Opoku Ware II was erected at the Suame Roundabout in 2004. During that period, it brought a certain charm to the Roundabout that new buildings even couldn’t dare. The pomp and pageantry that characterized it, especially during Christmas was breathtakingly awe-inspiring. It brought character to we the young ones then.

Apart from improving the appearance of Kumasi city, the free standing statue represents a particular version of history — it is given prominence and authority. The statue portrays a smaller-than- life size King handsomely cast in gold, majestically standing on a ceramic tile pedestal within the biggest Roundabout in West Africa.

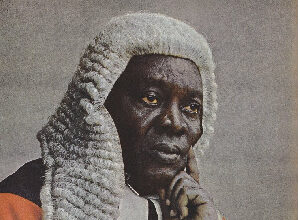

Anytime I chance upon the statue, what quickly comes to mind is the late King’s aura of refinement and achievements. For the sake of those who do not know, it is Otumfuo Opoku Ware II that opened the first Automatic Long Distance Dialing Exchange in Ghana when he was the Minister of Transport and Communications in the 1960s. As an architect, he designed and supervised the construction of the present National House of Chiefs building, surveyed and demarcated the lands for the Prempeh College, Opoku Ware Senior High School and Kumasi College of Technology, now KNUST. Otumfuo Opoku Ware II’s statue reveres his magnificence and towering legacy as an architect, a minister of state and a King.

The current occupant of the Golden Stool, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, is also honoured with statues for his meritorious service and achievements. The King is loved and cherished by all, including his critics. He has gotten his fair share of statues. The first one was erected and unveiled in 2016 to mark the 17 years of his reign. The 15-feet-tall bronze statue positioned inside the Airport Roundabout is a lovely, ingenious piece by all standards.

The second one is sited at the redeveloped Kejetia Market Roundabout. Erected in 2019, it remains the biggest statue in Ghana. It was unveiled to commemorate Otumfuo’s 20th anniversary. However, it caused a national uproar — not about the personality of the Great King, but the somewhat not-too-brilliant work by the sculptor. Otumfuo’s statue adds to the many works of art around the world. Although the occiput, the cloth and ornaments adorning the statue are phenomenal, the frontal face remains the subject of controversy. Asantes adore their King and will not accept anything below standard.

The ensuing debate and uproar should remind us of the importance of history, art and culture. Like history, art is inherently disputatious — challenging, provocative and exciting. If we can make people from all walks of life associate with the monuments and warm them to a mental excursion of history in all its richness, its purpose would then be achieved. It is said that “memory is the treasure house of the mind wherein the monuments thereof are kept and preserved”.

The monuments we see everyday speak to us. They are to emotionally help us connect with our cultural roots and traditions. But I wonder how many pedestrians commuting the Kumasi Central Prisons Roundabout at Adum, knows of that. Within the beautiful roundabout, one will unmistakably see the age-old statue of a man in a traditional cloth standing on a leopard beating gong-gong in a well-kept lawn. According to Nana Safo Kantanka Osei Bonsu a historian and researcher at Manhyia Palace, the monument represent an occasion in which Otumfuo Osei Agyemang Prempeh II, Asantehene, was born and named Barima Kwame Kyeretwie because a leopard was caught alive on his birthday. The controversy surrounding this specific monument is the animal used — instead of a leopard, the artist used a lion.

As an authentic records of history, citizens sometimes take these historical monuments for granted. I must say I am a victim to that, too. What about you dear reader? I guess we’re in the same boat together. As an avid cultural enthusiast, I am embarrassed to admit this: I have been to the Adum Ecobank to transact business on several occasions. Right next to Ecobank is the famous Opoku Trading Supermarket – adjacent is the Electricity Company of Ghana, Ashanti Region Headquarters. In between them is the iconic Prempeh II Street, a point of convergence of architecture, history, business and culture.

Standing proudly at the peak of a quaint long and hilly roundabout is the statue of Otumfuo Sir Osei Tutu Agyemang Prempeh II, the 15th monarch of the Asante Kingdom, reigning from June 1931 to May 1970.

As I took some of my time off to observe the monument, the begging questions that emanated were: Do monuments matter in our part of the world? Does it get the necessary attention? Does anyone even see it? Do they even know of the history of the personality and his contribution to the sustenance of Asante Kingdom? Does it get media publicity? After several thoughts of realizing my helpless feeling, it was tossing back the attitude of our leaders. After the ribbons have been cut and the cultural and political speeches have concluded, how much do we notice the monuments in our midst? Do they continue to proclaim the significance of the individual that they commemorate, or do an occasional event that brings memories to the monument?

My sense of discovery ended with the statue at Santasi Roundabout. I have walked pass the Santasi Roundabout many times, but for the life of me I can’t recall noticing the Otumfuo Osei Tutu I statue. I guess I haven’t been paying attention to the monument. Besides, city authorities have also failed raising awareness about such an important historical monument. Portraying smaller-than-life size statue, it is not hugely terrific (which might even account for receiving low attention). In our part of the world, statues are like that. We create them at vantage points and then forget them. It is not that we no longer set eyes on them, but rather we no longer pay attention. They pale into insignificance amidst moving vehicles and gigantic billboards along the roads.

In this contemporary era, cities and towns are making concerted efforts to erect, save and project their historical monuments so that their cultural heritage does not suffer. Kumasi’s royal monuments were dreamed up and largely funded by private citizens and supported by the traditional council. However, as soon as they are erected, it becomes public memorials.

The monuments are very precious. Their proper maintenance and projection are also essential to enhance their life. Most of the inhabitants either do not know the history behind these monuments or have forgotten them long ago. In his book, “The Ghosts of Berlin”, Brian Ladd clearly identifies societal recognition of monuments and nationwide memory. Ladd demonstrates that “how these structures are seen, treated, and remembered sheds light on a collective identity that is more felt than articulated.” In light of this, city authorities, must come out with a renewed concrete programs and events to draw the attention of the unsuspecting public to these vital monuments.

Source: Emmanuel Jewel Peprah Mensah|Contributor