The horror shocker that set off a culture war

“The ultimate experience in gruelling horror”: so suggests the subtitle of Sam Raimi’s infamous, brilliant film The Evil Dead (1981). Made when the director was just 20 years old, Raimi’s calling card quickly earned its place in the horror pantheon with its mixture of extreme gore, sly humour, and technical trickery. Now, more than 40 years on, the film’s lineage continues with a growing body of sequels that includes Evil Dead Rise, the fifth film in the franchise, written and directed by Irish filmmaker Lee Cronin, that is released next week. But all the while, the original remains a landmark work, which still has the power to scare, influence and entertain.

More like this:

– The horror that still terrifies, a century on

– The mysterious power of the ‘eerie’

– Why The Devils is still being censored

The Evil Dead is a love letter to genre cinema. Based originally on Raimi’s short film Within the Woods (1979), the film perfectly embodies the “lost in the woods” genre cliché – a popular trope in horror films that sees characters isolated in woods where evil of various forms dwells. It tells the story of five 20-somethings who make the mistake of holidaying in a lonely wooden cabin. In its basement, they discover a cursed tome called The Book of the Dead, subsequently summoning spirits from Hell.

With its tongue firmly in cheek, The Evil Dead focuses on the bloody trials of leading man Ash (Bruce Campbell) as his nearest and dearest are demonically possessed (Credit: Alamy)

Leading man Ash (Bruce Campbell) is then forced to watch as his sister Cheryl (Ellen Sandweiss), his partner Linda (Betsy Baker) and his friends Shelly (Theresa Tilly) and Scott (Richard DeManincor) succumb to violent demonic possession, something that can only be halted by bodily dismemberment. The question for Ash – aside from which implement is best to hack apart the possessed – is whether he’ll survive the night.

Nowadays, Raimi’s film is rightly celebrated for its innovations, as well as a legacy that includes, previous to Evil Dead Rise, two sequels by Raimi himself, a remake by Fede Álvarez in 2013, and a television series, Ash vs. Evil Dead (2015-2018). With all of this success, Christopher Brown, host of the Video Nasties Podcast and a great Evil Dead admirer, is unsure whether it sits so comfortably as a cult film today. “I’m loath to call The Evil Dead a cult classic,” he tells BBC Culture. “How big is your cult if you’ve got two sequels, a successful remake, computer games, comics and a three season TV show off your back?”

In spite of its status as an accepted great today, however, The Evil Dead generated a great deal of controversy upon its release in the UK in particular, where it got swept up in a heated debate.

The “video nasties” furore

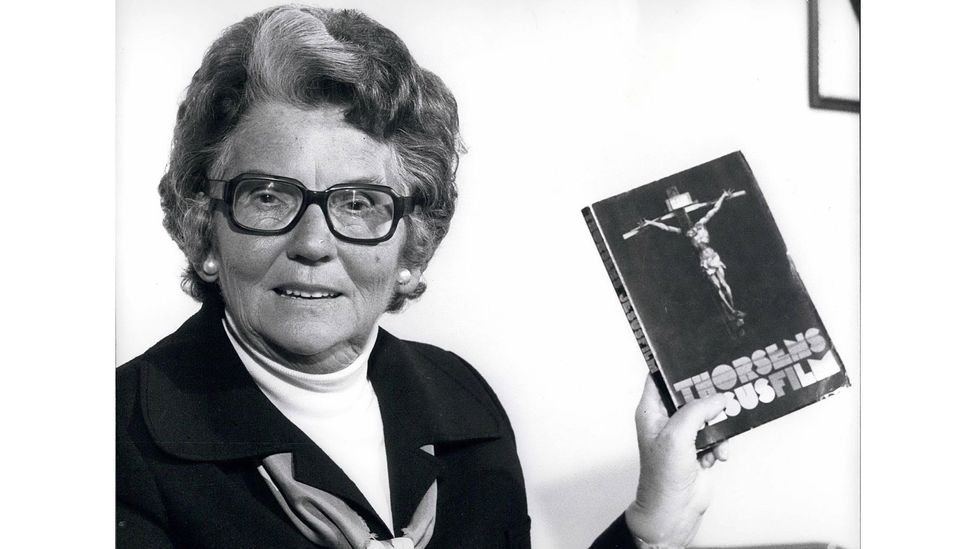

The 1980s “video nasties” saga in the UK saw a number of low-budget horror films threatened with prosecution under British obscenity laws if distributed on VHS. These films came under fire in particular from the conservative pressure group the National Viewers and Listeners Association and its founder, campaigner Mary Whitehouse. It was she who first coined the term “video nasty” and in doing so, ironically, created a perfect brand for the enticingly prohibited works. Though clearly made with its tongue firmly in its cheek, The Evil Dead arguably became the most famous “video nasty”, and its status as a possibly obscene film led to various bans, attempted prosecutions and all manner of controversy, not just in the UK but around the globe.

After the film had its first screening in Raimi’s hometown, Detroit, in October 1981, sales agent Irvin Shapiro took it to Cannes the following year, and managed to secure several European deals, in spite of multiple rejections from many major US distributors. This led to a successful British cinema release on 16 January 1983, which came after the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) passed it with an X certificate and 49 seconds of cuts. Only then did the film receive a wider release in the US, in April 1983.

The violence in the film is visceral and memorable, but it is the creativity on show that is arguably its main draw

But the film’s success really came about due to its swift release into the home entertainment market: it did particularly well in the UK, where the VHS was made available just a month after its cinema release. It topped the charts, becoming the best-selling tape of the year. “UK audiences embraced it and made it a big hit,” Raimi remarked in 1988. “After that the United States said ‘What’s that little horror picture that’s doing so well over there?'”

Unlike previous “cult” movies – such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show, whose popularity had blossomed via midnight screenings – The Evil Dead’s reputation was tied to its VHS release and the word-of-mouth effect that caused. In a post-lockdown age, where home viewing and theatrical releases have become more symbiotic out of necessity, The Evil Dead feels like a historic trailblazer in that respect.

However, all was not well for Raimi. Whitehouse famously labelled The Evil Dead “the number one nasty”, and later in 1983, chose segments of The Evil Dead to be screened in the House of Commons in one of several attempts to lobby the government into action against the video industry. She was outraged by a loophole which meant films could be released in Britain on VHS without vetting, censoring or classification by the BBFC – even though, in The Evil Dead’s case, the VHS version was the same as that approved by the BBFC for cinema release.

British moral campaigner Mary Whitehouse dubbed The Evil Dead ‘the number one nasty’ and led the charge against it (Credit: Alamy)

The Evil Dead, along with other video nasties, was then put on a list of films deemed to be “obscene”, and its VHS distributors Palace Pictures found themselves prosecuted. They successfully defended themselves, but the following year a new piece of legislation changed the game once more. The Video Recordings Act clamped down further on the distribution of “video nasties”, with the act’s author, Conservative politician Sir Graham Bright, declaring among other things that he believed research was taking place that “will show that these films not only affect young people but will affect dogs as well”.

In light of this, The Evil Dead had to be resubmitted to the BBFC for VHS classification, who refused to give it one (as it was still potentially threatened with further local prosecutions), and so it was withdrawn from sale and didn’t appear again until 1990. Even then, the BBFC still required further cuts beyond those undertaken for the previously passed cinema release. After several attempts throughout the following decade to get the film released uncut, in March 2001 the BBFC conceded that tastes had changed in the intervening years: the film was finally released uncut with an 18 certificate.

The film also ran into trouble in other countries. The original video was quickly banned in Finland after its initial home release in 1984. West Germany also took great exception to the film, and banned it not long after its theatrical release in 1984, in spite of initially passing it. When Britain released the film uncut in 2001, it took German authorities only a few months to again ban this new restoration. It wasn’t until 2017 that the film was finally released there uncut. Even then, it took criticism of Germany’s response from author Stephen King to change things.

Reflecting on the treatment of The Evil Dead, 40 years on, it’s interesting to note just how misunderstood the film was. The film’s knowingly over-the-top tone was lost on the censors, who deliberately approached it with the sort of po-faced, obtuse seriousness often present when demanding the banning of artwork on moral grounds.

Its remarkable artistry

The Evil Dead is a conjuring trick of a film, as well as a shocker. With the help of cameraman Tim Philo and special effects artist Tom Sullivan, Raimi utilised an array of low-budget techniques to create a gut-wrenching experience. The film’s shoot was arduous, made difficult by its low-tech effects, limited budget and an isolated location in very cold weather. “It was freezing,” Raimi told IGN in a 2015 interview. “When you’re in that cold for 16 hours… I started to die. There was no food, and everything was covered in Karo syrup in that temperature.”

The violence in the film is visceral and memorable, but it is the creativity on show that is arguably its main draw. Aside from the effective jump-scares and the occasional button-pushing gore, the film is an effective post-modern enterprise that fully embraces absurdity and horror history.

Inside the cabin, fragments of dead creatures hang from the ceiling in an ode to Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). A sound effect of clocks chiming is the same stock sound heard in George Pal’s horror-tinged adaptation of HG Wells’s The Time Machine (1960), and the stop-motion animation of the demons’ messy demise certainly feels like a nod to the famous stop-motion death of a Morlock in Pal’s film by special effects artist Wah Chang. In the basement, a torn poster for Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977) can be seen, itself a nod to Craven’s use of a poster for Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) in his own film. Raimi and Craven would continue referencing each other’s work, with The Evil Dead seen playing on a television in Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984).

New sequel Evil Dead Rise relocates the action from a woodland cabin to a Los Angeles apartment block – but retains the gore and black comedy (Credit: Alamy)

In spite of its referential nature, Raimi’s film still feels deeply original. Its tricks and effects have a hand-made quality that makes it raw and startling, a film as close to the work of Jean Cocteau (in particular in its water-mirror effects where a pool of water is used to create a mirror which can be entered)as to Hooper’s or Craven’s. Its first-demon perspective shots that feature throughout are also incredibly accomplished, especially considering that the technology used to create them was simply a greased-up piece of wood acting as a homemade steadicam.

Equally, for all its incredibly effective dread – its jump-scares are some of the most accomplished in cinema – it’s easy to forget just how well the film’s black comedy works. Though humour is foregrounded more in Raimi’s sequels, it’s actually more effective when housed within a film that is really invested in the horror as well. Ash’s famous line “Shut up Linda!” after being goaded by his possessed, cackling partner is still one of the great, if unfortunate, Having-a-Bad-Day moments of horror.

The Evil Dead is now seen as a classic horror, and rightly so. Many hold it as a frame of reference and I’m sure plenty of young filmmakers would love to replicate its success – Christopher Brown

The film’s most infamous moment is a sexual assault committed against Cheryl by a possessed tree. This scene in particular landed Raimi in hot water, and is often cited as the main reason why the film was variously censored and banned in different countries. In a 1988 episode of The Incredibly Strange Film Show, a British TV series devoted to the appreciation of B-movies, Raimi expressed regret about including it, saying “It was unnecessarily gratuitous and a little too brutal”. Surprisingly, the scene has literary influences: the film’s producer Rob Tapert suggested it was directly inspired by Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and Great Birnam Wood seemingly coming to life.

Today, the controversy around The Evil Dead has dissipated, and it is instead highly regarded as a seminal work, a testament to Raimi’s determination, as well as his innovation as a filmmaker. “The Evil Dead is now seen as a classic horror, and rightly so,” Brown concludes. “Many hold it as a frame of reference, and I’m sure plenty of young filmmakers would love to replicate its success.” The influence of the film became apparent almost straightaway – it’s difficult to conceive of, say, the early splatter comedies of Peter Jackson such as Bad Taste (1987) and Braindead (1992) without it.

Equally, its success can be judged by the way the franchise it started has endured. Interestingly, Raimi and his original star and producer Campbell and Robert Tapert have all played a role in the production of Evil Dead Rise, which shifts the setting from traditional backwoods cabin to a Los Angeles apartment block, showing the potential further scope of the Evil Dead cinematic universe. Early reviews for the film have been raves, suggesting it could well be a box office hit too. Meanwhile the original Evil Dead is still the benchmark for young horror filmmakers to this day. It’s the perfect urtext for those eager to give viewers a bumpy turn in the woods, even more than 40 years on from when its cursed VHS caused nightmares for the righteous and censors alike. And, quite possibly, their pets too.

Evil Dead Rise is released in US and UK cinemas on 21 April

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.