What nine rare 1800s photos reveal about US history

A new exhibition documents American photography’s first 70 years, exploring the US during a period of immense social, geographical and industrial change.

Modern culture is indebted to photography. “We can’t be literate in today’s world if we don’t know how to make and share and interpret images”, Jeff Rosenheim, photography curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, tells the BBC. “And when did camera culture become so much a part of all of our lives? It actually started in the 1840s and 50s.”

Though originating in Europe, “the speed with which this medium took hold in the US is one of the great surprises,” says Rosenheim, who, thanks to the incredible range of early American images in the William L Schaeffer Collection, a recent gift to the museum, saw an opportunity “to tell an expanded story about the birth of this medium”.

The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910, which opened on 11 April, documents American photography’s first 70 years through 225 photographs, reversing the usual top-down approach by focusing on unknown makers that tell nuanced stories about the US during a period of immense social, geographical and industrial change.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection“I quickly realised that there was fantastic picture-making, really important stories, outside of the big cities, all across the country,” says Rosenheim. One such story is embodied in an anonymous 1950s daguerreotype (an image created on silver-coated copper plate) of a young man holding a chicken − a man for whom a painted portrait was probably unaffordable. But, thanks to this new art, he had made his way to a studio, along with his feathered companion, to receive his likeness.

Holding the pose – sometimes for minutes rather than seconds − was essential to a good image, and the bird’s minimal blurring suggests it was at ease in the boy’s arms. Though photography was in its infancy, the sharpness of the image, from the boy’s freckles to the rooster’s scaly feet, is remarkable. The young farmer’s photograph captures the spirit of the American pioneers and is filled, says Rosenheim, “with pride and optimism for his own future”.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionIt would be another decade before the US would abolish slavery, and a century before the Civil Rights Act prohibited racial segregation. As a result, the theme of agency is implicit in many of these early images. An 1850s daguerreotype of a woman wearing a tignon (cloth turban) is a reminder of the Tignon Law in colonial Louisiana that required free black women to cover their hair. In response, some women reclaimed the tignon as an object of beauty and pride. This elegant portrait, with its extraordinary detail − from the delicately carved earrings to the weave in the translucent shawl − provides an opportunity for positive self-representation against a background of racial discrimination and negative stereotyping.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

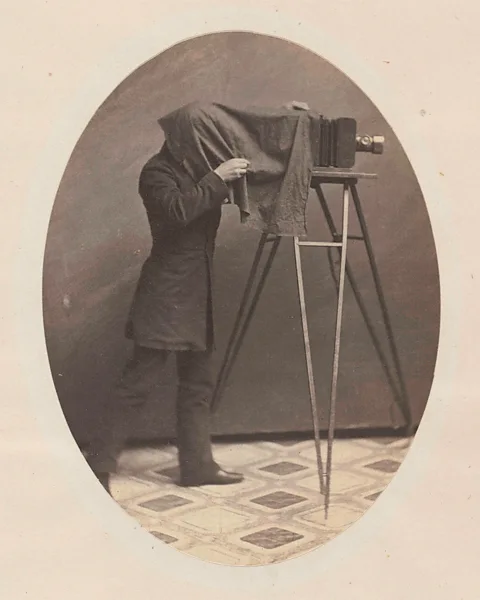

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionFor the 19th-Century US, the making of these images was a spectacle in itself. In a rare photograph printed on salted paper around 1855, we see this wizardry at work. “There’s this sort of magic about photography, that you have to go into the box itself, in a certain sense, and cover your head to make a picture,” says Rosenheim. But for all the photographer’s mastery, they are never entirely in control. Edward’s Steichen’s famous 1903 portrait of JP Morgan is an example; it inadvertently conveys his impatience with posing, and an innocent object – the chair handle – appears like a dagger in his hand.

“The world coalesces and comes together in ways that the photographer intended and did not,” says Rosenheim. “A painter can always redo things. They can add and subtract. A photographer, until recently, had to accept what the film or the plate recorded.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

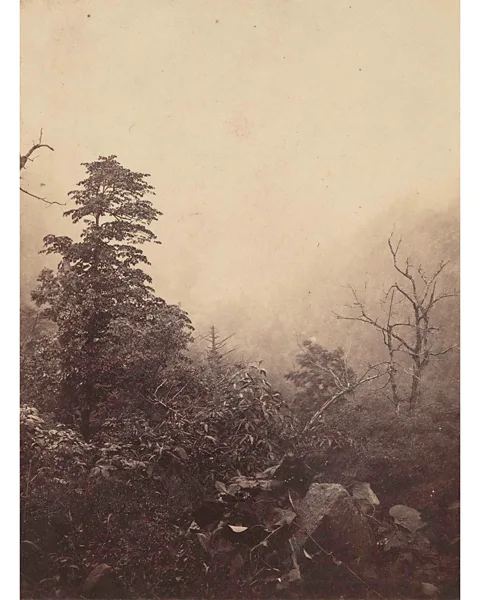

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionThough the miracle of photography captured America’s imagination, it was still deemed inferior to fine art. Pioneers such as John Moran, who came from a family of artists, challenged this by demonstrating the medium’s creative potential and the unacknowledged artistry involved in making images. “It is the power of seeing and deciding what shall be done, on which will depend the value and importance of any work, whether canvas or negative,” he argued in an essay published in The Photographic News of 1848. In his landscapes, we see a more atmospheric, ethereal quality that goes beyond realism to emphasise mood and emotion. “There are hundreds who make, chemically, faultless photographs,” he asserted, “but few make pictures.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

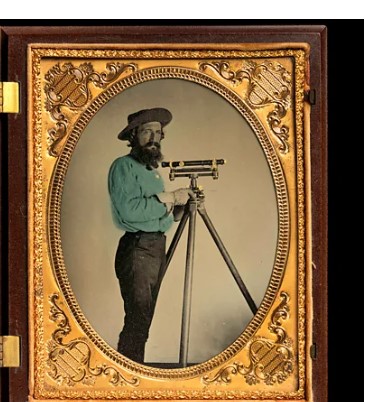

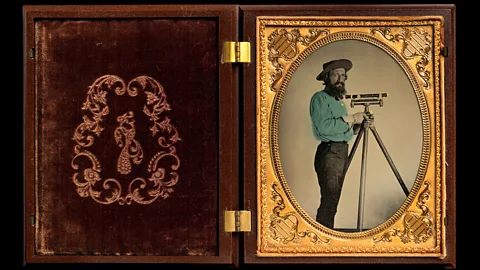

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionWhile the daguerreotype was indebted to France, the tintype – an image created on blackened iron – was an American invention. Producing high-quality results at a low cost, with no need for a studio, the tintype, peddled by itinerant photographers, meant remote communities and those of limited means could now also take part.

The broadening of access was reinforced by the industrialisation of the US, with the railroad and the telegraph connecting distant corners of the country – to the detriment of the Native American population who were pushed into ever-decreasing spaces. This geographic expansion, supported by topographic photography, is encapsulated in a c 1870 tintype of a man, perhaps a railroad worker, with his surveying equipment. Occupational portraits such as this, featuring workers with the tools of their trade, were a popular way to show the pride people took in their work and how they were contributing to the burgeoning American society.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionIn an 1870s tintype of a boy posing with a cornet, it may be an interest or talent, rather than a career, that this tiny keepsake records. On the left is a lock of his hair, fastened with paper flowers, possibly from his first haircut or perhaps obtained post-mortem. It was not uncommon for families to employ a photographer to memorialise a deceased loved one who had never been photographed before. Photography is “very linked” to life and death, says Rosenheim. A photograph is always younger than we are, always reminds us of our mortality, but at the same time preserves us in time.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

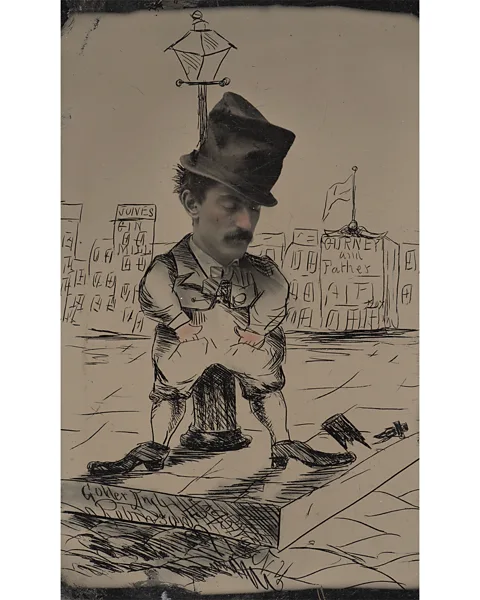

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionAs sitting for a portrait became more commonplace, novel experiences were sought. In a self-deprecating, comical tintype from the 1870s, the sitter’s headshot is surrounded by an imagined scene scratched into the metal plate. The studio was Golder & Robinson, on Broadway, New York City, also known for its photographs of public figures that people would collect in the form of “cabinet cards'” – slender photographs mounted on card.

“Cartomania” as the craze became known, “was somewhat driven by Queen Victoria, who sat for her portraits and everyone wanted them,” says Rosenheim. The introspection of the self-portrait era was running alongside the dawning of a culture of celebrity, with “everybody collecting pictures of everybody else”.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionWhile Golder & Robinson were distributing images of the good and the great, Alice Austen would use photography to speak up for the marginalised. She documented the daily lives of impoverished children, street sellers, and immigrants; and, as a queer women in a society that saw no place for same-sex relationships, questioned gender norms with her satirical images of women in the arms of other women, larking about in their underclothes or dressed as men.

Several of these photographs involve Austen’s close friend Trude Eccleston, who features in an 1888 silver print of a boat trip on Lake Mahopac. There’s a charming complicity as a smiling Eccleston locks eyes with the photographer. The gaze goes unnoticed by the dozing men, one of whom Eccleston would eventually marry.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer CollectionCarleton E Watkins was a gold prospector who moved from New York to California to seek his fortune, but instead of taking from the landscape, made a career of photographing it, recording the humbling scale of its mighty glaciers, waterfalls and canyons. This awe was intensified by the stereograph experience, where two slightly different images were viewed through a stereoscope to create a 3D effect. In Watkins’ picturesque View on the Columbia River (1867), the felled trees in the foreground hint at the impermanence of the US’s breathtaking landscapes.

As Miles Orvell writes in American Photography (2003): “Nature, in this 19th-Century context, was land to claim and defend in the name of the US government, it was a wild land to be exuberantly explored, mined, and mapped… And it was spectacularly beautiful.” But photography was beginning to cast a critical eye on what this nascent civilisation was doing to this ancient wilderness.

“If the mood of the 19th Century was an essentially optimistic one, happy in its discovery and exploitation of the American continent,” continues Orvell, “the 20th Century began gradually to wake up from that dream, look around, and see everywhere the destructiveness of the machines that had invaded the garden.”

The stories the camera told about the US and its people, argues Rosenheim, “entered their consciousness in a way that no painting or sculpture, or other forms of art, ever have”. Most of the pictures in the exhibition have never been published and offer fresh insights into early photography’s role in the making of America. This, Rosenheim says, has proved instructive. “The more we release things that are not known, the more we learn about our own history.”