The prison where inmates are short of food, space and uniforms

IMAGE SOURCE,GLENNA GORDON/AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

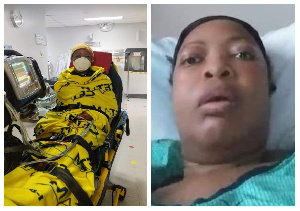

IMAGE SOURCE,GLENNA GORDON/AMNESTY INTERNATIONALWhen the food ran out for inmates at Liberia’s main prison earlier this month it exposed the terrible conditions that have long existed in the country’s jails.

The lack of supplies affected all of the country’s 15 prisons, forcing two to stop taking any new inmates.

It was only after at least two days that a local philanthropist and a charity stepped in to make up for the shortfall, but the wider problems – overcrowding and a lack of funding – have not gone away.

At Monrovia Central Prison, which overlooks the Atlantic Ocean, about 1,400 people are crammed into a space that was initially built for less than 400.

The outside of the prison has been given a facelift and the shining light grey walls could mislead passers-by into thinking that things are equally bright inside.

The food crisis gave a group of convicts, who briefly met journalists during a ceremony to open a new visitors’ hut, a rare opportunity to vent their frustration.

Now in his third year in prison, one man, convicted on rape charges, hissed repeatedly as he explained the frustration over the lack of food.

“The government feeds us one plate [of rice] every day; one time a day,” he said.

As he spoke, over a dozen others nodded, the anger and frustration visible on their faces.

IMAGE SOURCE,GLENNA GORDON/AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

IMAGE SOURCE,GLENNA GORDON/AMNESTY INTERNATIONALThe man in charge of Monrovia Central Prison, Varney G Lake, admitted that the overcrowding alone amounted to a “human rights violation”.

He also decried the poor infrastructure and the lack of well-maintained facilities in an interview with a local newspaper, FrontPage Africa.

When the food shortage struck, Upjit Singh Sachdeva, a well-known businessman living in Monrovia, who had already been providing some food from his resources, rushed to the city’s prison with emergency rations to calm the anxiety.

Better known as “Jeety”, he told the BBC that his assistance was “intended to help with the inmates’ transformation process”.

Besides, he said his religious beliefs mean that “when you have food, you share with others”.

His latest gesture was followed by other interventions including one from advocacy group Prison Fellowship Liberia which delivered rice and oil.

But in the long run, the authorities cannot continue to rely on charity to sustain the prison service.

‘All our prisons are obsolete’

The national director of prisons, Rev S Sainleseh Kwaidah, confirmed that the lack of proper food for prisoners was one of the many challenges he faces.

He blamed the shortfall on delays in the government releasing funds that should be supplied monthly.

For example, the money intended for food in September was only received after Christmas, he told the BBC.

As a result, prison superintendents had to “go on borrowing money here and there” to feed inmates.

One of the problems, Rev Kwaidah said, was that the only item in the national budget dealing with prisons was labelled “prison subsistence”.

“[The] prison budget must include feeding, accommodation, medication, operation, maintenance, refurbishment for wear-and-tear.

“All the prisons we’ve got in this country now are obsolete, these include the Monrovia Central Prison; they need to be repaired,” he added, the emotion clearly audible in his voice.

IMAGE SOURCE,GLENNA GORDON/AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

IMAGE SOURCE,GLENNA GORDON/AMNESTY INTERNATIONALHe also highlighted the lack of medical facilities and proper uniforms for both the inmates and warders.

The last batch of prisoner uniforms supplied by the UN was more than 10 years ago.

And there are no vehicles or fuel to escort prisoners.

“As I speak to you, we escort prisoners to many of our prisons on ‘kek-keh’ [motorised tricycles],” he said. These do not have doors, so are not ideal to transport convicts.

The vehicles the UN had left at the completion of its peacekeeping mission more than six years ago “have burned out and broken down”.

Justice Minister Frank Musa Dean, who is responsible for the penal system, told the BBC that the government was aware of the scale of the problems because they had been highlighted in an official audit.

But he did not have a short-term fix.

“We trust that the legislature will allocate the required funds and resources to address them,” he said.

Chance for rehabilitation

In 2011, the government drew up a 10-year plan to improve the facilities and Mr Dean said that though this “is being implemented… there are challenges” including the fact that the prison population has almost doubled.

Also, in a country where many people go hungry, there might not be much sympathy for inmates. However, the prison system is supposed to be for rehabilitation as well as punishment.

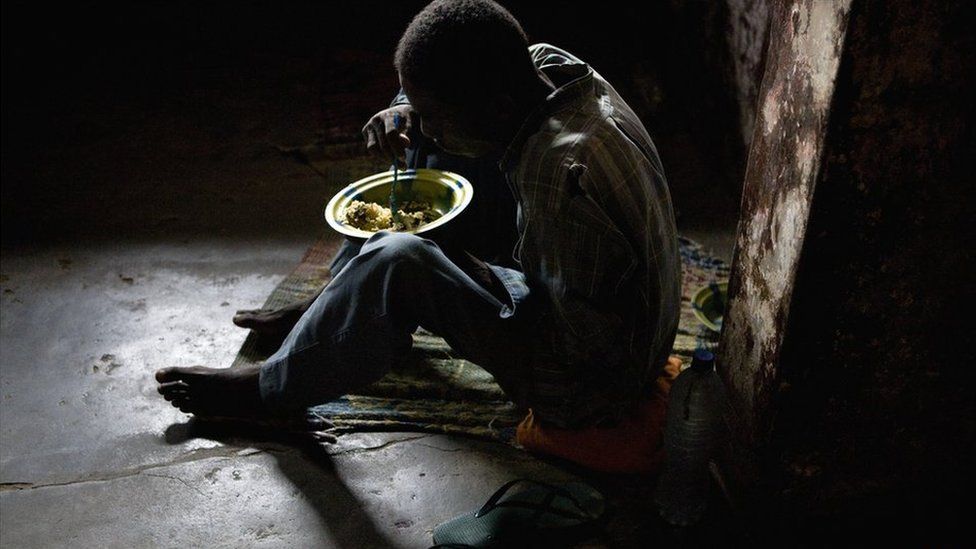

In some cases, prisoners are being used to help improve the infrastructure employing new skills that could help once they are freed.

IMAGE SOURCE,JONATHAN PAYE-LAYLEH/BBC

IMAGE SOURCE,JONATHAN PAYE-LAYLEH/BBCA recent project at Monrovia Central Prison recruited inmates to build the visitors’ hut inside the prison compound.

Dressed in dark blue track suits donated by the Unity Alliance Incorporated charity, they were allowed to assemble outside their cells to dedicate the hut.

The convicts told the BBC they wanted to send a signal that they should be given a second chance.

Jonathan, a 37-year-old convicted murderer who has been in the prison for eight years, said he was proud to have taken part in the renovation work.

He admitted he was “a kind of violent person outside, but I was worked on and my mind is now refined.

“I sat down, saw and regretted my action, I asked God first for forgiveness and tried talking to the people that I offended.”

“And as God is answering, things are working in that direction.”But when it comes to major changes in the prison system Jonathan, and others, may be waiting a long time.

BBC