Sudan crisis: 40 bodies pulled from Nile, opposition says

Forty bodies have been pulled from the River Nile in the Sudanese capital Khartoum following a violent crackdown on pro-democracy protests, opposition activists said on Wednesday.

Doctors linked to the opposition said the bodies were among 100 people believed killed since security forces attacked a protest camp on Monday.

Reports said a feared paramilitary group was attacking civilians.

Sudan’s ruling Transitional Military Council (TMC) vowed to investigate.

Residents in Khartoum told the BBC they were living in fear as members of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) roamed the streets. The paramilitary unit – formerly known as the Janjaweed militia – gained notoriety in the Darfur conflict in western Sudan in 2003.

“Forty bodies of our noble martyrs were recovered from the river Nile yesterday,” the Central Committee of Sudanese Doctors said in a Facebook post.

An official from the group told the BBC that they had witnessed and verified the bodies in hospitals and that the death toll now stood at 100.

A former security officer quoted by Channel 4’s Sudanese journalist Yousra Elbagir said that some of those thrown into the Nile had been beaten or shot to death and others hacked to death with machetes.

“It was a massacre,” the unnamed source said.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPOn Wednesday, the head of Sudan’s Transitional Military Council (TMC), General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, apologised for the loss of life and called for resumed negotiations – reversing a statement the previous day in which he said dialogue was over.

But a Sudanese alliance of protestors and opposition groups rejected the invitation. One of its leading members said the TMC could not be trusted.

The deputy head of the TMC defended the violent suppression, claiming that the protesters had been infiltrated by rogue elements and drug dealers.

“We will not allow chaos, we will not allow chaos and we will not go back on our convictions. There is no way back. We must impose the respect of the country by law,” said Mohammed Hamadan – also known as Hemedti.

What is happening in Sudan?

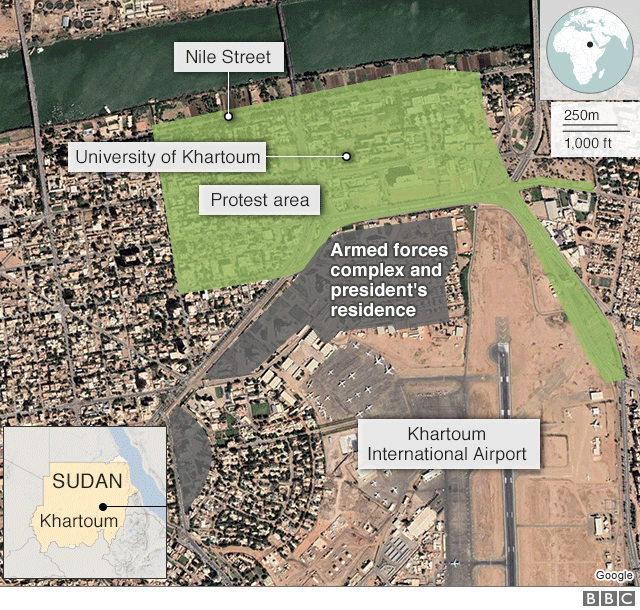

Demonstrators had been occupying the square in front of the military headquarters since 6 April, days before President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown after 30 years in power.

Their representatives had been negotiating with the TMC and agreed a three-year transition that would culminate in elections. But on Monday, forces swept in and opened fire on unarmed protesters in the square.

On Tuesday, Gen Burhan announced that negotiations with protesters were over, all previous agreements were cancelled, and elections would be held within nine months. Demonstrators had demanded a longer period to guarantee fair elections and to dismantle the political network associated with the former government.

International condemnation of the crackdown was swift and on Wednesday Gen Burhan made another televised speech in which he said the TMC was willing to resume negotiations.

Protesters had called for the Islamic festival of Eid al-Fitr, marked on Tuesday and Wednesday this week, to be celebrated in the streets, as a gesture of defiance against the military.

But much of Khartoum is under lockdown. Witnesses said protesters had retreated to residential areas where they were building barricades and burning tyres.

Sudan’s old politics re-emerge

Sudan’s military has faced international condemnation for its attack, but there were clear signs this was likely to happen. The country has been driven backwards by a military elite intent on holding on to power.

The TMC has scrapped agreements reached with the opposition Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), saying this will speed up the transition to democratic elections. That plan is likely a fiction.

The military also enjoys another advantage. In an age of international division, the notion of an “international community” pressuring the regime is fantasy. Sudan’s crisis has exposed the reality of international politics – that force can have its way, without consequence, if the killers and torturers represent a valuable asset to other powers.

It is impossible to say whether the FFC can come back as a street-driven force. What will not change – in fact what has been deepened – is the alienation of people from their rulers.

What have residents said?

Protest organisers, the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), accused the TMC of carrying out “a massacre” and urged its pro-democracy supporters to continue protesting peacefully.

“We have reached the point where we can’t even step out of our homes because we are scared to be beaten or to be shot by the security forces,” one Khartoum resident told the BBC.

Another resident, who also asked not to be named, said he was pulled from his car by members of the Janjaweed and beaten on his head and back.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPA pharmacist who spoke to the BBC from Khartoum said RSF troops were shutting down hospitals to prevent civilians receiving treatment.

“They kicked us out from two hospitals that were giving aid to the injured and the victims of the gunshots,” he said. “It’s an order from the military council to shut down those hospitals because we were giving aid for the citizens.”

A woman, identified only as Sulaima, told the BBC that troops from the Rapid Support Forces were “all over Khartoum”.

“They’re surrounding neighbourhoods, they’re threatening people. They’re also using live ammunition. They’re everywhere. We’re not feeling safe and we don’t have trust in the security forces. It’s complete chaos.”

Large numbers of heavily armed troops were also reported on the streets of Omdurman, Sudan’s second-largest city, just across the River Nile from Khartoum.

- How protesters keep going during Ramadan

- The art fuelling Sudan’s revolution

- ‘Why Sudan is shooting medics’