Nasa: Artemis Moon rocket second launch attempt called off

The US space agency has had to postpone the launch of its new Artemis I Moon rocket for the second time in a week.

Controllers were unable to stop a hydrogen leak on the vehicle, almost from the start of Saturday’s countdown procedure.

Nasa now has another opportunity to launch the rocket on Monday or Tuesday.

After that the vehicle will have to return to its assembly building for inspection and maintenance, which will mean further delays.

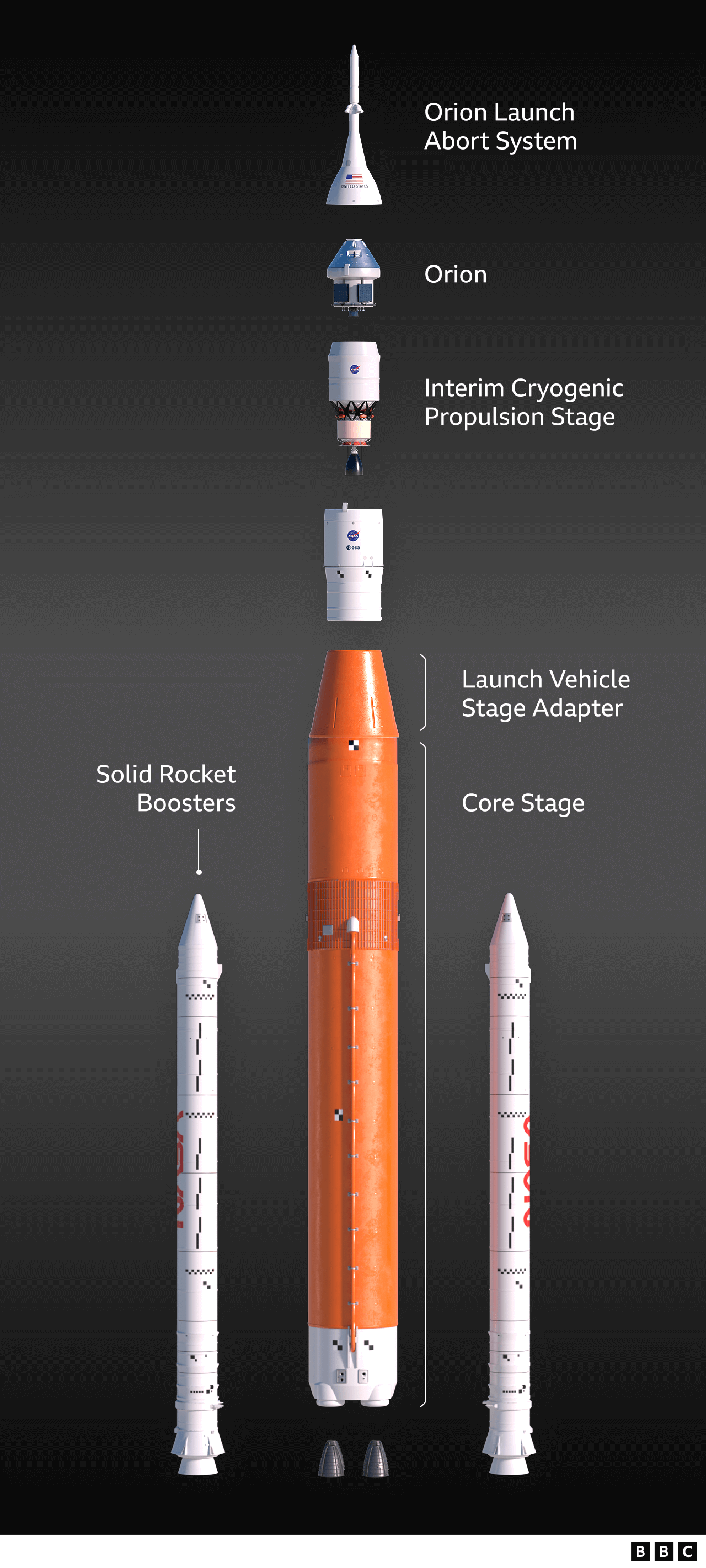

The Space Launch System is the most powerful rocket ever developed by Nasa, and is designed to send astronauts and their equipment back to the lunar surface after an absence of 50 years.

Much of the SLS’s enormous thrust comes from burning almost three million litres of super-cold liquid hydrogen and oxygen in four big engines on the vehicle’s underside.

But when controllers sent the early morning command to fill the rocket’s hydrogen tank, an alarm went off, indicating there was a leak.

The problem was traced to the connection where the hydrogen was being pumped into the vehicle.

Controllers tried a number of fixes, including allowing the hardware to warm up for short periods, hoping this might reset the seal. But without success.

The Artemis I mission is an uncrewed demonstration, but Nasa Administrator Bill Nelson said the rocket’s future role in human spaceflight meant extreme care was still required in its operation.

“We will go when it’s ready,” he stressed. “We don’t go until then, and we make sure it’s right before we put humans up on the top of it.”

It’s possible Nasa could try again in the next few days. But there are battery systems on this rocket that will soon need inspection. And if the vehicle has to be rolled back to the engineering building for further work, it could be mid-October before we see it again on the launch pad.

Nasa astronaut Zena Cardman said she understood everyone’s frustration but they should recognise the challenge of working with super-cold propellants.

“Liquid hydrogen is a fickle substance; it’s difficult to handle. But the fact that we’re able to get this much data is really, really helpful. I think we’ll be able to resolve this issue in the future. Every time we encounter an issue, it makes us that much wiser the next time,” she told BBC News.

Saturday’s attempt to despatch the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket had been scheduled for the start of a two-hour window beginning at 14:17 local time (19:17 BST; 18:17 GMT).

The 100m-tall vehicle’s objective is to hurl a human-rated capsule, called Orion, in the direction of the Moon, something that hasn’t happened since Project Apollo ended in 1972.

Nasa first tried to launch SLS on Monday, but that bid was ultimately scrubbed because controllers couldn’t be sure the four big engines under the rocket’s core-stage were properly prepared for flight.

When the SLS does get away, it is sure to be a spectacular sight.

“It’s gonna be ‘shuttle on steroids’,” said Doug Hurley, who was the pilot on the very last shuttle mission in 2011.

The former astronaut now works for Northrop Grumman who make the big white solid boosters on the sides of the SLS.

“What I always thought was the coolest thing about shuttle launches was you saw it lift off and it was well clear of the tower before you heard anything, and then it was even a little longer before you felt it,” he explained.

“Thrust to weight-wise, SLS is pretty close to what shuttle was. Apollo’s Saturn V rocket was drastically different. I never saw it in person but it lumbered clear of the pad. For shuttle, it seemed like it was clear in an instant, almost as soon as the boosters were lit. SLS should be the same,” he told BBC News.