Mr Congeniality: Julius Malema calms down and puckers up to kiss frogs in his ultimate quest for presidency

The maturing but no less ambitious EFF leader is running an excellent political campaign, even as polls suggest party support is declining. However, what is clear is that Malema wants to be head of state and, at 43 years old, he has the time to make that a medium-term goal.

EFF leader Julius Malema has emerged as one of the stronger contenders on the election campaign trail, cutting a figure more considered and less fury-filled than in previous campaigns.

His lavishly funded campaign also means the party runs the town’s best poster and outdoor advertising game. EFF posters and massive billboards outstrip the ANC by an order of magnitude. But it is the change in Malema that is most apparent.

South Africa’s most extensive pre-election poll, for the defunct Change Starts Now movement, showed that he is liked and feared in almost equal measure. The EFF’s support has plateaued because South Africans are middle-of-the-road voters, sensible even, and they have never turned to the extreme right or left in any significant electoral trend line.

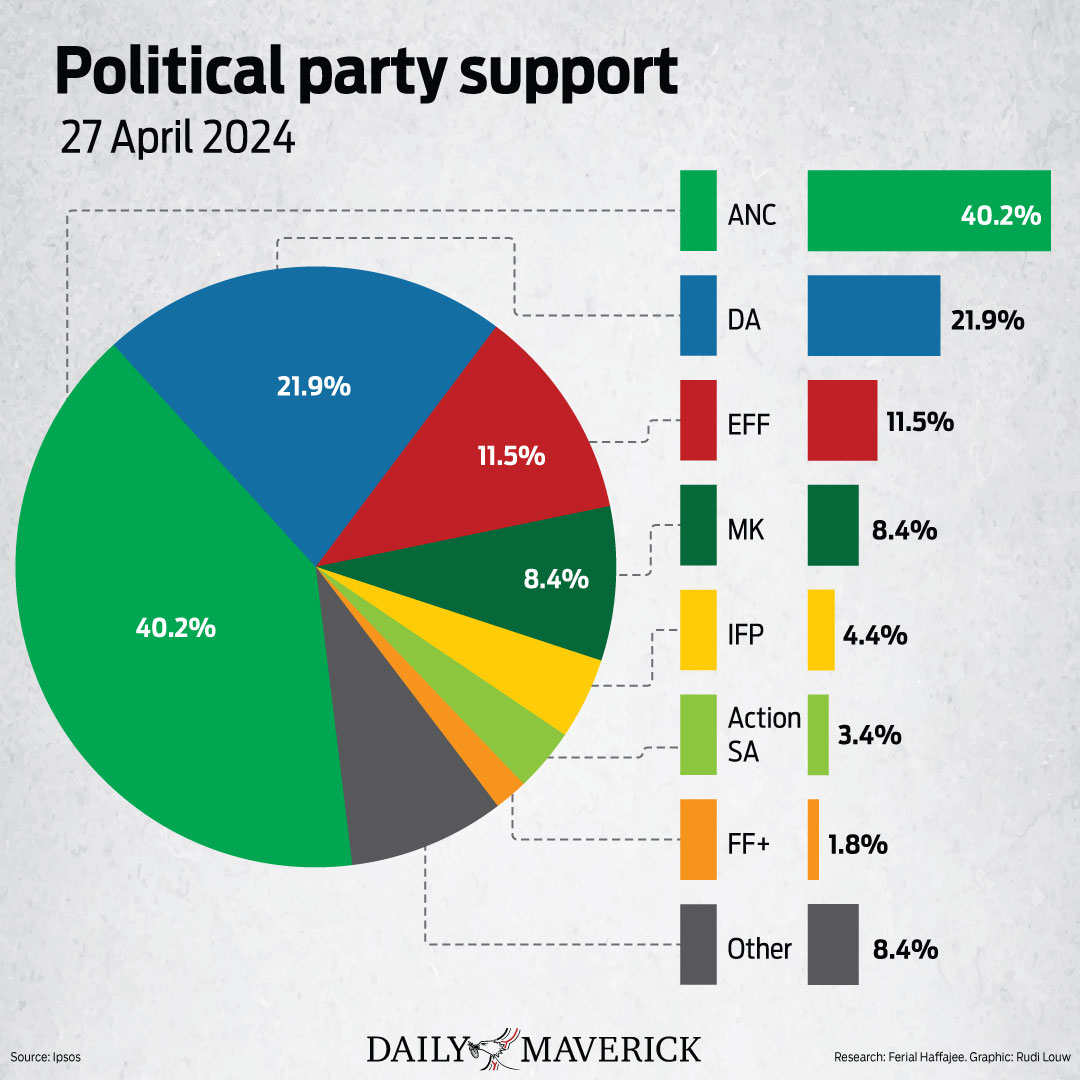

The latest Ipsos poll released at the end of April suggests that the EFF will get 11.5% of the national vote, down significantly from previous surveys. The MK party appears to be taking a chunk of both EFF and ANC support.

Daily Maverick has found that Malema has toned down his violent rhetoric to present a more considered and often humorous picture on the campaign trail. We report here on two recent EFF events.

Wits School of Governance

At the Wits School of Governance in April, in a conversation with Professor Adebayo Olukoshi, Malema revealed that he thinks the EFF’s natural coalition partner is the ANC. Dressed in a tailored black shirt, he had traded in the EFF red T-shirt to cut a more statesman-like figure.

He had also stopped shooting from the hip and used an iPad to consider answers to questions and direct his discussion.

The ambitious politician clearly wants to be the president of South Africa, and an ideal result for him after the 29 May elections would be for the EFF to emerge second.

“When you run, you always want to be number one or you want to be number two,” he said. “You can’t be number three.”

With neither option looking likely, what could happen instead is that the ANC and EFF will form a coalition government in Gauteng if the governing party loses its provincial majority. The two parties have already partnered to run two metro governments.

In Johannesburg, the placeholder mayor, Al Jama-ah councillor Kabelo Gwamanda, is a compromise between the two parties. In Ekurhuleni, the EFF has been given the most powerful portfolios in return for agreeing that an ANC mayor should lead the industrial heartland city.

“The ANC are unreliable partners,” said Malema, though he added that Gauteng would “inevitably” be led by a coalition. “When the ANC loses, it loses forever, like it did in the Western Cape and Joburg.”

EFF leader Julius Malema and Mbuyiseni Ndlozi at a community meeting on 28 April 2024 in Daveyton, South Africa. (Photo: OJ Koloti / Gallo Images)

From Gauteng, a national coalition with the ANC is a possible next step for Malema if Deputy President Paul Mashatile succeeds President Cyril Ramaphosa. Malema and Mashatile are part of a band of political brothers who are still close. This group also includes ANC Secretary-General Fikile Mbalula, who is a good friend of the EFF leader, though they may spar publicly.

Even if the business community and markets are spooked by an ANC-EFF coalition, its potential is clearly front and centre in Malema’s strategy to get to the Union Buildings. Part of the ANC supports a coalition with the EFF. At the same time, Ramaphosa’s supporters in the ANC believe that such a coalition will cause an existential crisis for the culture of the old liberation movement.

But the ANC and EFF campaigns in Gauteng are intersecting and, for six months, the governing party in the province has refused to break a coalition with the Red Berets, defying the resolutions of its National Executive Committee.

“Even if I were sports minister [in a coalition Cabinet], I would be like the president. The ANC will lean to the left if we are the official opposition. Ourselves and the ANC must get 50% of the vote [for a shift to the left],” said Malema, explaining his coalition strategy.

Malema said the ANC is now a rural party dependent on super-majority wins in Limpopo, Mpumalanga and the Free State to get more than 50% nationally. If it doesn’t, Malema has lined up to form a coalition.

Pundits say the ANC’s most likely national coalition now is one with small parties with which it has relationships and has entered into municipal coalitions, including Patricia de Lille’s Good, the African Independent Congress of Johannesburg Speaker Margaret Arnolds, Al Jama-ah, and perhaps the IFP.

Another natural ANC ally, the IFP, is in a coalition arrangement with the DA, ActionSA and nine other parties in the Multi-Party Charter (MPC) Coalition. This week, News24 editor-in-chief Adriaan Basson floated the idea of IFP leader Velenkosini Hlabisa as a presidential candidate if the MPC gets enough votes.

But if the ANC gets only the 40.2% – or thereabouts – predicted by Ipsos’ latest poll, it could force a more straightforward coalition with the bigger EFF.

What was clear from the Wits conversation is that Malema wants to be head of state and, at 43 years old, he has the time to make that a medium-term goal.

“We are going to kiss a lot of frogs along the way [to attain a strategic objective]. We are patient,” he said, adding: “The ANC is not a small organisation. You have to eat it bit by bit.”

Julius Malema at a Freedom Day rally held on 27 April in Alexandra, Johannesburg. (Photo: Luba Lesolle / Gallo Images)

Malema did not highlight the most radical policy planks of the party’s manifesto, such as the nationalisation of mines, banks, the rest of the financial sector and the South African Reserve Bank. Instead, he focused on the insourcing of government security guards and on changes to the intergovernmental distribution of power as priorities.

“[You need] a supermetro called Gauteng. Local government receives the smallest chunk of budgets. If you were to give Panyaza [Lesufi, the Gauteng premier], with the energy he has, implementation power, [that would change things].”

Premiers have limited ceremonial and patronage power in the present system, even if provinces get the most significant chunk of the budget. Most of this spending goes to schools and hospitals in a ring-fenced budget. The National Development Plan also proposed a reconfiguration of powers to change how services are delivered by considering the reduction of provinces.

Another area the EFF leader focused on was changes to the minimum wage. The EFF manifesto proposes increasing the minimum wage to R6,000 a month with further increases in specific sectors. (The current minimum is about R4,500 a month for general workers.)

The EFF’s plans for power are to show through demonstrating how it can lead. Malema believes, and the EFF manifesto lists, what it says is evidence of how it can be a good government. But its efforts in Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni are chaotic at best.

“The EFF will demonstrate in practical terms how it governs,” he said.

Supporters of the EFF attend a Workers’ Day community meeting in Hammanskraal, Pretoria, on 1 May. (Photo: Alet Pretorius / Reuters)

Meeting with the Khutsong and Merafong communities

In May, Malema was in Westonaria, Carletonville, in the gold mining towns of Khutsong and Merafong. A 3,000-strong crowd waited patiently for hours for the “commander-in-chief” or “Juju”, as the MCs called him.

When he arrived in his convoy, he was wearing a black shirt and a red beret. Local leaders put a red campaign bib over his shirt. It advertised the policy planks of the party’s manifesto in bullet points: “expropriation of land without compensation”; “nationalisation”; “building state and government capacity”; “free education, healthcare, housing and sanitation”; and “massive development of the African economy”.

On the stage, Malema is a natural. He spoke without notes or the iPad for about an hour, his voice a little hoarse from a long and busy campaign trail. Because people can’t eat nationalisation and probably don’t care too much about prescribed assets, the applause went to more bread-and-butter promises and local issues.

Khutsong is beset by sinkholes and it is the biggest issue for the residents, who suffer from the ground collapsing under their roads and on their properties. To loud cheers, Malema spoke about these holes, which the Gauteng government has promised to fix, but has yet to do so. He cloaked all his points in the promise of a return to dignity.

“Gauteng is what it is because of this place,” he said, referring to the area being one of the country’s gold belts. “The gold is in London, and Carletonville is nothing. They took your minerals that would have given you a better life.”

The riff against the mines was also popular with the crowd.

Malema promised a “worker in each and every house”, like Mmusi Maimane of Build One South Africa does. The promise to do away with the basic state-sponsored RDP houses and to replace them with three-bedroom houses with a dining room and an indoor toilet got wild applause, displaying the human desire for a nice home.

“When your friends call you, you must [be able] to give them directions to your house [with pride],” Malema said. Amid the loud cheering, a man shouted: “Dankie, Juju. Dankie, Papa.”

What Malema has in spades is the common touch and knowledge of touchpoints that trouble the average black South African: work, dignity at work, a system that often feels like it is structured against you by favouring the connected, and the desire to be connected to the land through owning a piece of it.

One of his stories that clearly touches many is when he speaks about the practice of burying the umbilical cord to symbolise a human being’s connection to the land where they are born.

“This land belongs to me. Once I get the land, I will build myself a beautiful house on this land,” he said in Carletonville, telling people how they should think about ownership.

“Once you are the owner, you will be able to say [to people who don’t speak to you nicely]: ‘Repeat that thing again; I didn’t hear you properly.’ That’s what landlessness does – it takes away your dignity,” he said, neatly twinning land with dignity, one of the constitutional cornerstones.

Who’s funding the EFF campaign?

Unlike most other parties, the EFF does not submit its funders lists to the Electoral Commission of SA (IEC), as it must under the requirements of the Political Parties Funding Act. The IEC can force it to do so, but has never done so.

What’s clear is that the party has money. Its rally to start the campaign, during which Malema was lifted by a scissor lift à la a Beyoncé concert, was all extravaganza and glitz that cost a fortune.

The party’s posters are among the best examples and are plastered everywhere. Its mobile vans for rallies are state-of-the-art, with sound systems and a stage that can turn a piece of veld into a mega event, as was apparent in Carletonville.

Asked by Olukoshi who was funding the campaign, Malema said Standard Bank had advanced it a loan against the funds the party would get from the fiscus. In addition, 1,100 party members who earn a government salary are giving a percentage as tithes. It also received R37-million from the IEC, which disperses political funds to represented parties.

Malema said the EFF had applied for a R100-million loan from the bank, which had approved R60-million.

“We said, sharp, bring it.”

The loan is commercial, with Standard Bank getting paid by debit order as soon as the IEC funds land. Malema said it was used to pay service providers for the launch rally. “We are in talks with the bank again,” he added.

Malema lives like the president he wants to be in a lifestyle entirely out of kilter with his MP salary. He bats away any questions about his proximity to and close friendship with cigarette boss Adriano Mazzotti, who is widely believed to sponsor the five-star lifestyle he and Malema share like brothers.

He also bats away any questions about how Venda-based VBS Mutual Bank was a cash cow for his lifestyle until it was reported by Daily Maverick. Malema again denied any impropriety by any EFF member in relation to the VBS scandal, but the evidence is all there to read in the collected VBS works by Daily Maverick investigative journalist Pauli van Wyk.

Source: DM