How Tupac wrote the ultimate anthem for single mothers

The iconic 90s hip-hop artist was known for his pained intensity. But Dear Mama, a tribute to his mother Afeni, showed off his softer side – and still brings listeners to tears.

“Not everyone is so lucky and gets to experience the love of a mother for a long time,” explains DJ Master Tee, whose words are staggered due to deep emotion, before he starts to cry down the phone.

“A lot of people’s mothers died way too early… and I think Tupac Shakur understood that well,” the producer continues. “He didn’t just want to make a song that celebrated the mothers who are here, but also the ones that passed away.”

DJ Master Tee made the original silky-smooth beat (which was later adapted by co-producer Tony Pizarro) for Dear Mama, the late rap legend Tupac’s candid tribute to the many sacrifices of his single mother Afeni Shakur. She was an activist in the radical political group The Black Panthers, who subsequently struggled with drug addiction and to make ends meet while raising her two children.

This song is the pained yet ultimately joyful epicentre of Tupac’s otherwise death-obsessed third studio album, Me Against the World, which was released 30 years ago this month. In the context of an album where Tupac shifts from suicidal (So Many Tears) to grief-stricken (Lord Knows), repeatedly using the word “hopeless”, Dear Mama feels like uncovering a diamond at the bottom of a pitch-black mine.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Even as a crack phene, momma / You always were a black queen, momma,” he famously rapped.

This lyric alone represented a radical shift in rap storytelling in the way it represented victims of the so-called Crack Era, when use of the drug soared across the US during the 1980s and 90s.

Previously, rap artists had stripped away the humanity of crack addicts via slurs such as “basehead” and “zombie”. But, Tee says, Tupac saw addicts “as victims of the state, who needed our support”. And although Tupac expresses sadness over a childhood with little money – where he and his sister Sekyiwa observed the matriarch of their family descend into the hell of addiction – he leads with empathy for Afeni Shakur’s struggle.

He chants out all his words with a bear-hug warmth, confirming that he never stopped seeing Afeni as a superhero. In celebrating her, Tupac serves to pay respect to the struggle of single mothers everywhere, as well as mothers full stop – a sentiment the whole world can appreciate. This is reflected in the numbers, with the song racking up over 345 million streams on Spotify alone. Indeed, Dear Mama remains one of the rapper’s most celebrated tracks: in 2009, it became the first song by a solo rapper to be inducted into the US Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry, awarded for its profound cultural significance.

“It really doesn’t matter if you grew up in the ghetto or not, because Dear Mama transcends all of that,” explains the song’s engineer, Paul Arnold. “You could be rich, poor, black, white, brown, whatever; you’ll find a way to relate to the song. Honestly, it’s difficult for me to even talk about it and not get choked up. It forces you to think about your own mother and that isn’t always easy. Behind all the controversy, it was obvious he was a very emotional guy.”

A revolutionary mother

To properly explore the creation of this song, you must follow the roots of the woman who inspired it. Born in North Carolina in 1947, Afeni Shakur (whose birth name was Alice Faye Williams) was confronted with racism from the start. This was a time where Jim Crow laws around racial segregation were bluntly enforced.

Afeni’s family moved to the Bronx when she was 11. Despite living in the diverse melting pot of New York City, she felt she was part of a system designed to push black people to the bottom of US society. She found solace hanging around local street gangs (including the Gangster Disciples) and subscribed to the “by any means necessary” approach of activist Malcolm X, who preached that black Americans should violently resist their oppressors in sharp contrast to Martin Luther King’s celebrated pacifism. After seeing the co-founder of the Black Panther party Bobby Seale speak at a political rally in 1968, Afeni was inspired enough to join, telling The New York Times in 1970 she was impressed by the way he spoke of the homeless leading their revolution: “I’d never seen that before.”

Afeni quickly rose through the ranks of the Black Panthers, pioneering a free breakfast plan for hungry schoolchildren and starting a protest campaign against exploitative landlords. The party won high-profile enemies including FBI director J Edgar Hoover, who ran surveillance on key members (resulting in the 1969 assassination of radical deputy chairman Fred Hampton) and considered the group a threat to the status-quo. In 1971, Afeni was one of 21 Black Panther members indicted by a New York grand jury, accused of plotting to shoot police officers.

From prison Afeni maintained a position of strength, writing in one unapologetic letter to the media: “We know that we live in a world inhuman in its poverty. We know that we are a colony, living under community imperialism. The US that we see is not one of freedom, beauty, and wisdom, but of fear, terror, and hate. We have no respect for your laws, taxes, your gratitude, sincerity, honour and dignity. You don’t respect us – thus we don’t respect YOU.” This defiance and righteous anger would be something her future son would directly channel into his rap career.

Getty Images

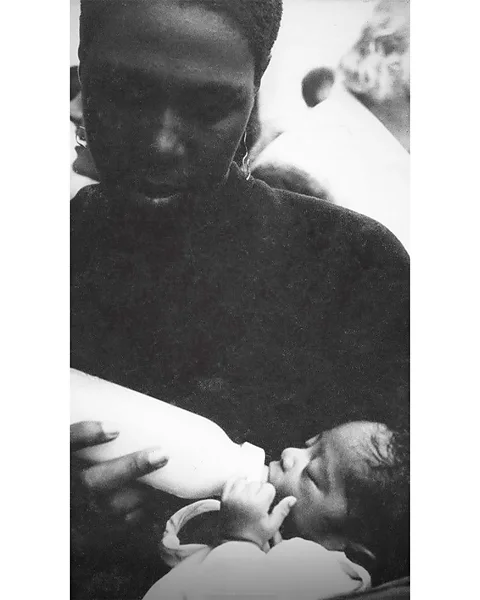

Getty ImagesHeavily pregnant and facing a 300-year prison sentence, Afeni refused legal counsel, choosing to represent herself in what was then the most expensive trial in the history of New York State. Despite the bleak odds, she won her freedom and was the driving force behind the Panthers being acquitted on all 156 counts. Born a month after the trial ended, her son Tupac Amaru was named after the Peruvian warrior who led the largest anti-colonial rebellion in Spanish American History. Right from his birth on 16 June 1971, Afeni’s boy had revolution and black nationalism pulsing through his veins.

Tupac’s complex childhood

Growing up in East Harlem, Tupac was often surrounded by enemies of the state. His stepfather Mutulu Shakur and step-aunt Assata Shakur were political rebels on the FBI’s Most Wanted List. A paranoid Afeni also taught her son how to spot undercover federal agents lurking outside their apartment building by observing their shaky body language and suspect sunglasses. If Tupac ever misbehaved, he would be punished by being forced to read The New York Times cover-to-cover.

His knowledge of global politics was at an advanced level long before his 10th birthday, and while the other kids read comic books, Tupac was learning how fear is more powerful than respect through reading Machiavelli’s The Prince. He also admired how his mother, to quote lyrics from Dear Mama, “made miracles every Thanksgiving” – cooking a wholesome meal despite working multiple jobs and living off welfare food stamps.

Afeni had on-off partners who served as role models to Tupac, but he never really had a stable father figure in his life, with biological dad (and fellow Black Panther) Billy Garland largely absent until later years. When the Black Panthers disbanded, Afeni, like so many of her peers, struggled to readjust to mainstream society. Years of being accosted by police led to her suffering PTSD, and during a choppy childhood living in New York, Baltimore, and Marin City, California, Tupac watched his mother’s sharp decline. She increasingly self-medicated with drugs to alleviate her pain.

A talented actor who could quote Shakespeare at will, Tupac secured a place at the coveted Baltimore School of the Arts. It helped push him away from trouble and family drama. But when the family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area due to financial problems, Tupac’s academic hopes dissolved into the ether. Converting the poetry he wrote to process childhood trauma into chart-topping raps became Tupac’s main focus; he saw himself as that rare rose which could grow through the harshness of the inner-city concrete.

Former DJ Billy Dee first met Tupac early on in his rap career, back when he was a member of the funk hip-hop collective the Digital Underground. They bonded during a 1989 tour that brought the group over to Berlin, where Dee’s family was also based. “He hated the German food and the big sausages,” she recalls. “I invited him back to my mom’s house and she cooked him fried chicken. My mom was a single mother and I remember he liked that about her a lot.”

She continues: “If you were with him, he would literally die to protect you. But he was so radically smart, too. My mom had photos with Yasser Arafat on the wall. Tupac, even as a young man, knew exactly who that was and spoke passionately during our lunch about supporting the historical struggle of the Palestinian state.”

FX/ Disney

FX/ DisneyA student of political emcees like Chuck D and Ice Cube, Tupac had similarly socially conscious lyrics, which passionately furthered Bobby Seale’s dream of a black community where should someone fall down, everyone else served as their crutches. He quickly was signed to Interscope Records and, on Tupac’s stirring 1991 debut album 2Pacalypse Now, the gut punch of a rap fable Brenda’s Got a Baby told the story of a teenage black girl who faces horrific neglect and abuse. It’s Dickensian in its three-dimensional dissection of society’s most forgotten casualties.

Yet the rising artist was also a magnet for controversy, and many couldn’t get past the palpable contradictions in his music. For every bluesy song that advocated women having full autonomy over their bodies (Keep Ya Head Up) or preached unity within gang neighbourhoods, there were more nihilistic street anthems where Tupac referred to women using offensive slurs and glorified shooting crooked cops. It was unclear whether he wanted to lead the revolution or simply press the self-destruct button.

From firing at two off-duty police officers harassing a black motorist (the charges were later dropped) in Atlanta, to being convicted for assaulting film director Allen Hughes, a fatalistic Tupac was often in the newspapers more for controversy than actual music. Going into the creation of his third solo album, Me Against the World, the artist desperately needed a song that showed a softer side.

‘Drop something for my momma’

DJ Master Tee remembers the night he gave Tupac the beat to Dear Mama well. After Tupac had just come off stage doing a landmark freestyle at New York’s Madison Square Garden alongside then-friend and fellow rapper The Notorious B.I.G. Backstage, Tee gave the rapper a cassette filled with beats. It didn’t take long until Tupac called him up, excited about one particular instrumental that was built around an interpretation of jazz keyboardist Joe Sample’s soothing In All My Wildest Dreams.

Master Tee had flipped this song’s lovelorn, slowly caressed keys by matching them with raw vinyl scratches. Tee knew his use of this sample would trigger something deep within Tupac and he likens its tone to a sunny afternoon spent reminiscing over family photos. On the original version, which was recorded in October 1993, Tupac opens by saying: “Yo, Master Tee, drop something for my momma!” Tee says the words flowed out of Tupac with “real ease” in the studio.

In a 1995 interview with the LA Times, Tupac said he had wanted to make the rap equivalent of Don McLean’s Vincent. “So it came out like this deep love ballad,” Tee says. “He was a machine with it! He would do a full song with three or four verses as well as a bridge and hook in one take, and it would sound perfect. I also worked with Prince and Tupac reminded me of him. They were both workaholics, who you never saw yawn once. There was a mission behind the music!”

In 2023, Master Tee, aka Terrence Thomas, filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against parties including Tupac’s record label Interscope and its parent company Universal Music Group claiming he was “never properly and fully credited with his publishing copyright from the writing and creation of the music of Dear Mama”. Last year, it was reported, Universal Music began the process of seeking the claim’s dismissal.

Engineer Paul Arnold, alongside the producer Tony Pizarro, was later asked by the label to make the song more timeless and radio-friendly. Although they kept the beat’s foundational sample, they added more instrumental layers as well as a syrupy R&B hook that interpreted the song Sadie by Motown group The Spinners. “They didn’t like what we turned in at first,” recalls Arnold. “But we persuaded them to live with it overnight. The next day we got a call like: ‘Don’t touch it!'”

Arnold met Tupac a few times in New York’s Quad Studios and was impressed by the way he took time to speak to everybody and hear out their life story. “He’d be interested enough to listen to the life story of the guy bringing in the coffee,” Arnold says.

Tupac tended to stack his vocals, recording three or four separate versions of the same verse, combining the various voices so his presence was more commanding and carried an eerie pull. It resulted in a voice that was gigantic and filled with duelling layers of pain; the raps were bellowed out like an ancient mountain-top God shouting down prophecies to his followers. However, Dear Mama was the rare track where Tupac had insisted on only one vocal track.

FX/ Disney

FX/ Disney“One of the reasons his voice sounds softer than usual on Dear Mama is because we pulled back on the vocal layering,” Arnold explains. “We wanted Tupac’s voice to have more of a direct feel, so it’s like a one-on-one conversation.”

Tupac, who raps: “I finally understand for a woman it ain’t easy trying to raise a man,” recognised that it was single mothers who shouldered the extra burdens working class boys racked up during their transition into men. He also pleaded for troubled young black males to forgive their mothers for any hardships, finding a way to exchange grudges for love and deep-rooted appreciation.

“Dear Mama proved that even the biggest gangsta rapper in America with Thug Life tattooed on his chest could still be super vulnerable,” says Arnold, who believes the fact Tupac’s vocals sound on the edge of tears remains the song’s biggest strength. “He really was more like a preacher than a rapper. He knew crying made you more of a man. I got to meet Afeni, when I worked on posthumous Tupac music later on. When we met, she gave me the biggest hug. All the love that’s inside Dear Mama made more sense to me after that.”

The purgative Dear Mama was a big hit, reaching the peak of the Billboard Rap Songs chart, just as the album went to number one too; it was accompanied by a music video, featuring Afeni beaming with pride while looking through old photos of her son. It’s still part of the cultural conversation years later: in 2023, FX released a TV docu-series bearing the song’s name and focusing on Afeni and Tupac’s rollercoaster relationship. At the time of Dear Mama’s release in 1995, Tupac was imprisoned on sexual assault charges, which he always vigorously denied, and still nursing five bullet wounds sustained in an ambush while visiting the same studio where he’d laid down Dear Mama vocals. The world didn’t know whether to see him as a pariah or an outlaw.

A lot has been made of the period that followed its release: Tupac was eventually bailed out of prison by the notorious Death Row Records’s CEO Suge Knight pending an appeal of his conviction, and his music took a more war-ready stance, culminating in his murder in a drive-by shooting on 7 September 1996 in Las Vegas. Yet for DJ Master Tee, it’s Dear Mama that best represents Tupac’s humanity. “It’s a really simple song and it’s very catchy, but this allowed it to resonate with more people,” he says. “It’s a song that will outlive us all. Whenever the grieving press play on Dear Mama, they’ll instantly be able to recall what a mother’s embrace feels like.”

This tribute to the dead was confirmed by a live performance of Dear Mama at a 1996 Mother’s Day charity benefit organised by Death Row Records for single mothers. The rapper explained to the cheering crowd: “[With this song] I want to talk about the people who don’t got mommas anymore. We sometimes forget to appreciate our mothers! But my little homie Mutah [Beale, who was a member of Tupac’s Outlaw Immortalz collective and, as a toddler, watched his parents get murdered in the family living room] hasn’t got no mother today. He can’t share in our smiles.”

It all goes back to something Tupac says on the song’s third verse: “And there’s no way I can pay you back / But my plan is to show you that I understand.” This proves Dear Mama isn’t just a song, but more a ritual; a sonic safe space for the listener to sit still and reminisce on their mother’s sacrifices. As Arnold concludes: “Tupac immortalises a mother’s love and their willingness to do whatever it takes to ensure their child is doing alright. That will always be powerful, no matter who you are.”