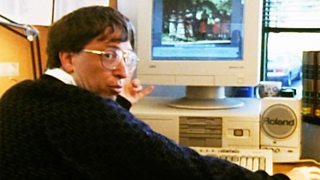

How Microsoft founder Bill Gates mapped out the new internet era back in 1993

Gates and Paul Allen launched computing giant Microsoft 50 years ago. In 1993, he talked to the BBC about the online innovations that would define the 21st Century.

When the BBC first broadcast an interview with Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates in June 1993, there were thought to be only 130 websites in total. The BBC’s venerable science programme Horizon was investigating the new “Electronic Frontier”, in an era where “information is starting to redefine our world, its geography and its economy”. Gates told the programme: “This is the information age, and the computer is the tool of the information age and software is what will determine how easily we can get at all of that information.” Viewers could send off a cheque for £2 and receive a transcript of the programme in the post.

The computer industry had already grown faster than any in history, but the key to future profits was creating something portable and user-friendly. The programme asked: “Do we need endless information, or do they just need to sell it to us?” In a world where a list of almost every website could fit on two sides of a sheet of paper, the world wide web did not even get a mention. However, the ideas explored in the programme are often far ahead of their time.

In the early days of Microsoft, Bill Gates and Paul Allen set a goal of having a computer on every desk and in every home – all running Microsoft products, of course. They first met as children at a private school in Seattle, where they discovered a shared love of computers. Both went on to college but dropped out and created Microsoft, so-called because it provided microcomputer software.

The company’s big break came in 1980 when Microsoft agreed to produce the operating system for the personal computer being developed by IBM, the world’s leading computer company at the time. In a stroke of business genius, Microsoft was allowed to license the operating system to other manufacturers, spawning an industry of “IBM-compatible” personal computers which depended on its MS-DOS product. The money had begun to roll in – and to this day it has not yet stopped.

Whoever is on the other end of that network knows what you’re watching on television, can get your credit card number, can know lots of things about you that you don’t want them to know – Denise Caruso

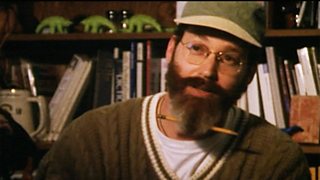

His departure from Microsoft also meant that he had more time to perfect his guitar moves. Legendary music producer Quincy Jones even claimed in a magazine interview that Allen “sings and plays just like Hendrix”. He said: “I went on a trip on his yacht, and he had David Crosby, Joe Walsh, Sean Lennon… then on the last two days, Stevie Wonder came on with his band and made Paul come up and play with him – he’s good, man.” The design of Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture, which he founded, has been likened to a smashed guitar and was created by superstar architect Frank Gehry.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAllen jumped ship from Microsoft before products such as Windows, Excel and Word ever made it into the world’s homes and offices. By the early 1990s, Gates’ vision for networked computers sent sales and profits soaring. However, the pair’s early dream of putting a computer running Microsoft software in every home and business was only half complete. Word processing and spreadsheets were lucrative, but Microsoft’s relentless drive to expand needed new worlds to explore. The next step was to bring multimedia into people’s homes, turning the personal computer into a communication device. It was the world of leisure so beloved by Allen that Gates needed to tap into.

1,000 TV channels, and nothin’ on

Gates acknowledged to the BBC in 1993 that “the home will be a tougher frontier to conquer”. However, he was confident that Microsoft would succeed. “If you take a time frame like 15 years or certainly 20 years, I have no doubt that the vision of a computer in every home, although it won’t look like today’s computer, will absolutely be achieved,” he said.

A year earlier, Bruce Springsteen had a hit grumbling about having “57 Channels (And Nothin’ On)”. Undeterred by the Boss’s cynicism, Microsoft’s Nathan Myhrvold talked of a future where we would have up to 1,000 television channels. He said: “That might sound like a nightmare, but I think it’s a wonderful thing. Imagine what your favourite bookstore would be like if there were only five books.” Describing a system resembling today’s streaming services, he spoke of an “online interactive guide, which uses computer technology to organise the channels, show them to you by topic, even learn of the material that you like to watch, and then present it to you in an online fashion right on the television”.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC’s unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Myhrvold was providing a tantalising glimpse of the future: a world at your fingertips where you could order an En Vogue CD or Prince tickets instantly. But what would this mean for personal privacy?

There was a warning in the 1993 programme from Denise Caruso, editor of the magazine Digital Media: “The ease of sitting in front of your interactive TV five years hence and being able to order something by pushing your remote control means information about you is going through a network. That means that whoever is on the other end of that network knows what you’re watching on television, can get your credit card number, can know lots of things about you that maybe you don’t want them to know.”

Caruso raised issues echoed in the current debate about Generative AI models being trained by devouring copyrighted material. She said: “By making information a commodity, you really change the nature of how people think about ideas and their work and what they do. I am a writer. My stock in trade is ideas, and when you try to draw lines around what information is and where did an idea come from and who had that idea originally and what napkin was it originally drawn on, when you start moving information into that realm, it starts to get very fuzzy about where one person’s idea stops and another one starts.”

She said that while information was an incredible commodity, it had no value at all unless it could be protected. But how could you protect something that has no physical existence and could be copied or changed undetectably?

“The problem is that the solutions are as complex as the problems themselves. Do you want to lock up all the information? Absolutely not. We would have no scientific progress if scientists weren’t able to freely exchange ideas and information. Do you just have a free-for-all and say all information is free? Well, you can’t do that either because people do actually make their livings upon the fruit of their work, [which] is information, whether it’s a book or it’s a movie or it’s music. I think technology is an incredible thing and it’s very powerful, but it’s powerful in both ways, and it’s very important that we all understand that before we just embrace it.”

The birth of email

While the world wide web did not feature in the programme, it was many viewers’ first introduction to the concept of electronic mail, or email. As Microsoft continued its voracious expansion, the company’s human resources vice-president Mike Murray said that email “creates an electronic village [which] allows us to transcend the borders of time or geographic barriers”. His words may seem grandiose now, but at the time it would have been a revolutionary idea that one could communicate instantly with someone or many people on the other side of the world without the need for an expensive international phone call.

By the end of 1993, the number of websites was estimated at 623, having doubled every three months. By the end of 1994, the figure was 10,022. Microsoft was seen by some commentators as being slow to acknowledge the possibilities and growth of the web, but in May 1995 Gates sent a memo to his senior staff titled “The Internet Tidal Wave”, calling it “the most important single development to come along since the IBM PC was introduced in 1981”. Three months later, Microsoft launched its web portal MSN alongside the release of Windows 95. Some versions had its brand-new Internet Explorer browser controversially bundled in. The future was again up for grabs, and Gates once again had some big thoughts on how he might conquer it.