Coronavirus: Iran cover-up of deaths revealed by data leak

The number of deaths from coronavirus in Iran is nearly triple what Iran’s government claims, a BBC Persian service investigation has found.

The government’s own records appear to show almost 42,000 people died with Covid-19 symptoms up to 20 July, versus 14,405 reported by its health ministry.

The number of people known to be infected is also almost double official figures: 451,024 as opposed to 278,827.

Iran has been one of the worst-hit countries outside China.

In recent weeks, it has suffered a second steep rise in the number of cases.

The first death in Iran from Covid-19 was recorded on 22 January, according to lists and medical records that have been passed to the BBC. This was almost a month before the first official case of coronavirus was reported there.

Daily number of deaths from Covid-19 in Iran

Official figures vs uncovered data, 22 January to 20 July 2020

Since the outbreak of the virus in Iran, many observers have doubted the official numbers.

There have been irregularities in data between national and regional levels, which some local authorities have spoken out about, and statisticians have tried to give alternative estimates..

A level of undercounting, largely due to testing capacity, is seen across the world, but the information leaked to the BBC reveals Iranian authorities have reported significantly lower daily numbers despite having a record of all deaths – suggesting they were deliberately suppressed.

Where did the data come from?

The data was sent to the BBC by an anonymous source.

It includes details of daily admissions to hospitals across Iran, including names, age, gender, symptoms, date and length of periods spent in hospital, and underlying conditions patients might have.

The source says they have shared this data with the BBC to “shed light on truth” and to end “political games” over the epidemic.

The BBC cannot verify whether this source works for an Iranian government body, or identify the means by which they gained access to this data.

But the details on lists correspond to those of some living and deceased patients already known to the BBC.

The discrepancy between the official figures and the number of deaths on these records also matches the difference between the official figure and calculations of excess mortality until mid-June.

Excess mortality refers to the number of deaths above and beyond what would be expected under “normal” conditions.

What does the data reveal?

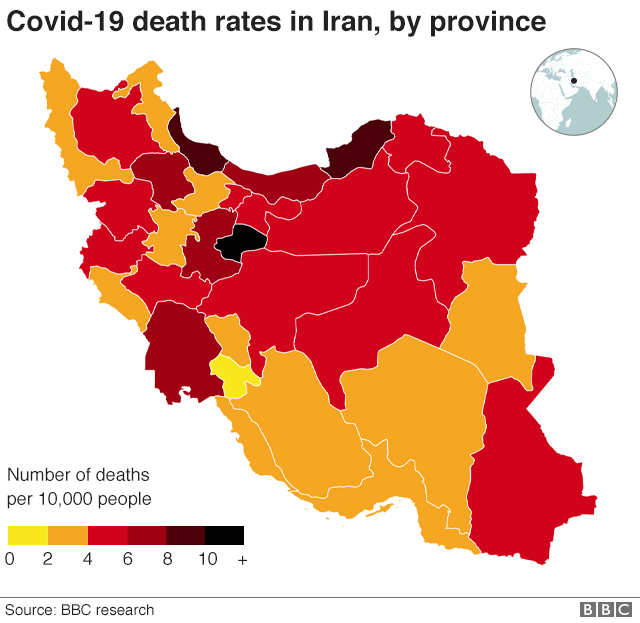

Tehran, the capital, has the highest number of deaths with 8,120 people who died with Covid-19 or symptoms similar to it.

The city of Qom, the initial epicentre of the virus in Iran, is worst hit proportionally, with 1,419 deaths – that is one death with Covid-19 for every 1,000 people.

It is notable that, across the country, 1,916 deaths were non-Iranian nationals. This indicates a disproportionate number of deaths amongst migrants and refugees, who are mostly from neighbouring Afghanistan.

The overall trend of cases and deaths in the leaked data is similar to official reports, albeit different in size.

The initial rise of deaths is far steeper than Health Ministry figures and by mid-March it was five times the official figure.

Lockdown measures were imposed over the Nowruz (Iranian New Year) holidays at the end of the third week in March, and there was a corresponding decline in cases and deaths.

But as government restrictions were relaxed, the cases and deaths started to rise again after late-May.

Crucially the first recorded death on the leaked list occurred on 22 January, a month before the first case of coronavirus was officially reported in Iran.

At the time Health Ministry officials were adamant in acknowledging not a single case of coronavirus in the country, despite reports by journalists inside Iran, and warnings from various medical professionals.

In 28 days until the first official acknowledgement on 19 February, 52 people had already died.

Who were the first whistleblowers?

Doctors with direct knowledge of the matter have told the BBC that the Iranian health ministry has been under pressure from security and intelligence bodies inside Iran.

Dr Pouladi (not their real name) told the BBC that the ministry “was in denial”.

“Initially they did not have testing kits and when they got them, they weren’t used widely enough. The position of the security services was not to admit to the existence of coronavirus in Iran,” Dr Pouladi said.

It was the persistence of two brothers, both doctors from Qom, which forced the health ministry to acknowledge the first official case.

When Dr Mohammad Molayi and Dr Ali Molayi lost their brother, they insisted he should still be tested for Covid-19, which turned out to be positive.

In Kamkar hospital, where their brother died, numerous patients were admitted with similar symptoms to Covid-19, and they would not respond to the usual treatments. Nevertheless, none of them were tested for the disease.

Dr Pouladi says: “They got unlucky. Someone with both decency and influence lost his brother. Dr Molayi had access to these gentlemen [health ministry officials] and did not give up.”

Dr Molayi released a video of his late brother with a statement. The health ministry then finally acknowledged the first recorded case.

Nevertheless state TV ran a report criticising him and falsely claiming the video of his brother was months old.

Why the cover-up?

The start of outbreak coincided both with the anniversary of the 1979 Islamic Revolution and with parliamentary elections.

These were major opportunities for the Islamic Republic to demonstrate its popular support and not risk damaging it because of the virus.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader, accused some of wanting to use the coronavirus to undermine the election.

In the event, the election had a very low turnout.

Before the global coronavirus pandemic hit, Iran was already experiencing a series of its own crises.

In November 2018, the government increased the price of petrol overnight and cracked down violently on protests which followed. Hundreds of protesters were killed in a few days.

In January this year, the Iranian response to the US assassination of top Iranian general Qasem Soleimani, seen as one of the most powerful figures in Iran after its Supreme Leader, created another problem.

Then Iranian armed forces – on high alert – mistakenly fired missiles at a Ukrainian airliner only minutes after it had taken off from Tehran’s international airport. All 176 people on board were killed.

The Iranian authorities initially tried to cover up what happened, but after three days they were forced to admit it, resulting in considerable loss of face.

Dr Nouroldin Pirmoazzen, a former MP who also was an official at the health ministry, told the BBC that in this context, the Iranian government was “anxious and fearful of the truth” when coronavirus hit Iran.

He said: “The government was afraid that the poor and the unemployed would take to the streets.”

Dr Pirmoazzen points to the fact that Iran stopped international health organisation Médecins Sans Frontières from treating coronavirus cases in the central province of Isfahan as evidence of how security-conscious its approach towards the pandemic is.

Iran was going through tough times even before the military showdown with the US and coronavirus hit.

The sanctions which followed Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal in May 2018 hit the economy hard.

Dr Pouladi says: “Those who brought the country to this point don’t pay the price. It is the poor people of the country and my poor patients who pay the price with their lives.”

“In the confrontation between the governments of the US and Iran we are getting crushed with pressures from both sides.”

The health ministry has said that the country’s reports to the World Health Organization regarding the number of coronavirus cases and deaths are “transparent” and “far from any deviations”.

BBC.COM