Check out the return of all the US’ lost language

Watson is part of a grass roots resurgence to revive Kouri-Vini, a historical name for the Louisiana Creole language that has been reclaimed to prevent confusion with other things “Creole”, such as ethnicity, musical styles and culinary traditions.

Watson’s next album, slated for release this summer, will be sung mostly in Kouri-Vini. Today, the language has fewer than 6,000 speakers, but at the beginning of the 20th Century, it was spoken by much of the Creole population in the 22-parish region of south-west Louisiana known as Acadiana.

This unique cultural pocket of the US is sometimes called Cajun Country, but long before the arrival of the Francophone Acadians, or Cajuns, from Nova Scotia in 1755, there was a much larger population of French-speaking Creoles – people with roots in Europe and Africa born in Louisiana.

Thanks in large part to a generation of musicians devoted to preserving it, a Kouri-Vini renaissance is underway. Watson, who performs all over the world, considers himself an ambassador of Creole culture and language.

Kouri-Vini has been reclaimed to prevent confusion with other “Creole” terms, referring to things like food and ethnicity (Credit: Rubens Alarcon/Alamy)

“When I joined this band in 2011, I just identified as African American, but now, through years of travel and learning, I also identify as Creole,” said Desiree Champagne, the washboard player in Watson’s band. “The importance of preserving the culture and identity is to understand who you are and where you come from, what you are part of.”

Kouri-Vini originated in Louisiana, but in the early 1900s, it spilled over the border to eastern Texas, Watson’s native state, and he grew up hearing elderly relatives exchange neighbourhood news in the language. As they died, Watson, who is African American, realised that his ancestral language was dying with them. He began using his stage as a platform to revitalise this language that is deeply rooted in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

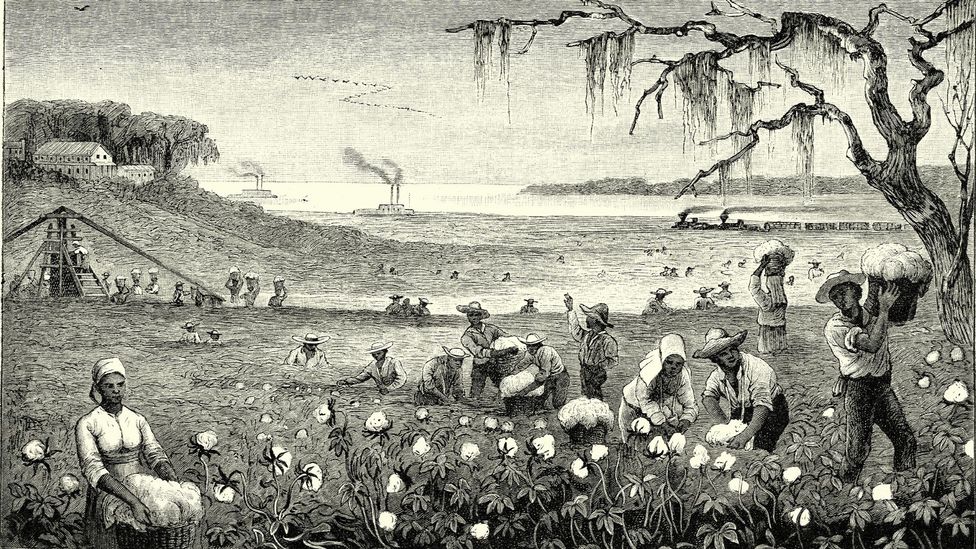

In the early 18th Century, newly enslaved people created an amalgam of their native West African languages and the French that colonists used to communicate on the Louisiana sugar and indigo plantations where they toiled. “It’s the first language all these Africans coming from different tribes and caste systems would speak when they were enslaved,” Watson said. “They had these pidgin languages they would speak for a couple of generations, but it eventually became an organised language, which is Creole (Kouri-Vini)” – whose name comes from the Creole pronunciation of the French verbs “courir” (to run) and “venir” (to come).

Watson not only keeps the language extant through his live performances, but on La Nation Créole, the radio show he hosts on Lafayette’s KRVS-88.7. He spins Creole grooves from Louisiana as well as from across the French Creole-speaking world, such as Haiti and Guadeloupe.

Traditionally, zydeco music has been sung in English, Louisiana French and Kouri-Vini (Credit: Tim Mueller)

Until recently, Kouri-Vini was disparaged as an inferior language spoken by the uneducated. “Most of society’s opinions about languages and language varieties are actually opinions about the people who speak them,” said Marguerite Justus, a linguist and Community Development Specialist at CODOFIL (Council for the Development of French in Louisiana). “If the people who speak a certain language or dialect are perceived as low status, then we are inclined to perceive their way of speaking as low status.”

Interestingly, not all Kouri-Vini speakers were people of colour. During the 19th and 20th Centuries, whites – especially white children – picked up the language from servants in their household. In Alfred Mercier’s 1880 “Study on the Creole Language in Louisiana”, the Louisianan poet and playwright explained that he spoke Kouri-Vini exclusively for much of his childhood because it was the language of his caregiver. His parents, however, disapproved of him speaking it.

The decline of Kouri-Vini started with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. When the Louisiana territory was acquired by the nascent United States, non-English speakers felt pressure to learn the language and culture of the new government, and it only increased with statehood in 1812. Kouri-Vini took another blow during World War One when speaking any language other than English was considered unpatriotic.

In the early 1900s, Kouri-Vini was spoken by much of the Creole population in Acadiana (Credit: Stockimo/Alamy)

Today, Louisianians are eager to reclaim this minority heritage language, and from students to distinguished scholars, there are movements to resurrect it.

For the past decade, a growing number of adults and children have been learning Kouri-Vini online. The Louisiana Historic & Cultural Vistas offers online Kouri-Vini classes that fill up quickly, partly because young people who grew up hearing their elders speak the language want to become fluent.

A new generation of speakers are also making podcasts, hosting TV shows and even writing books in Kouri-Vini. Though only 20, the self-proclaimed language activist Taalib Auguste started LA Créole Show on Télé-Louisiane, an online media channel in Lafayette, that promotes Creole culture. He even wrote a book in Kouri-Vini called Koushma (nightmare), inspired by the story of an enslaved man he heard from his grandparents.

Since Kouri-Vini was traditionally passed down orally, there are challenges to writing the language. There wasn’t a comprehensive approach until the Guide to Louisiana Creole Orthography was published online in 2016.

Kouri-Vini was developed by enslaved Africans on colonial plantations in Louisiana (Credit: duncan1890/Getty Images)

Oliver Mayeux, a linguist and research fellow at the University of Cambridge, contributed to the guide and has been a key player in the resurgence of Kouri-Vini. His father’s background was Louisiana Creole, so he’s passionate about preserving the language that is so closely tied to Creole identity.

“The genesis of a new language on the plantations of colonial Louisiana is testament to the fact that those enslaved people were just that, people. People with their own culture and traditions, hopes and dreams,” Mayeux said. “The language is a living link to that point in time. The stories of its speakers must be kept alive. Their words must be remembered.”

Mayeux and a group of colleagues collaborated on Ti Liv Kréyòl (‘Little Book of Creole’), the first book for Kouri-Vini learners published in 2020. It was illustrated by Jonathan Mayers, a Kouri-Vini speaker, artist and poet who works to elevate Creole culture and language.

These days, zydeco music is one of the best ways for travellers to encounter Kouri-Vini in south-west Louisiana. The feel-good tunes spill from front porches and backyard crawfish boils.

Zydeco offers a lively introduction into Kouri-Vini culture (Credit: Philip Scalia/Alamy)

Flannery Denny loves zydeco music so much, she moved to Louisiana from Upstate New York. “Music brings people together across lines that tend to divide people,” Denny said. “On the dance floor, age, geography and politics don’t matter. People are engaged in enjoying the moment.”

Corey Ledet, lead singer in the band Corey Ledet & His Zydeco Band, is another Grammy-nominated African American musician devoted to keeping Kouri-Vini alive. He can be spotted around Lafayette performing at the Feed & Seed or the Blue Moon Saloon, literally bending the accordion to his will, while simultaneously thumping a kick drum to produce the African-derived syncopated rhythms at the heart of zydeco dance tunes.

Growing up in Texas, Ledet often visited family in Parks, Louisiana, who spoke Kouri-Vini, but he was not encouraged to learn it. To become more proficient, he takes lessons from Herbert Wiltz, one of the founders of C.R.E.O.L.E Inc, (Cultural, Resourceful, Educational, Opportunities and Linguistic Enrichment Incorporated), a non-profit organisation that preserves and promotes Creole culture. Ledet attends Wiltz’s La Table Kreyol (Creole Table), which offers opportunities for learners to practice conversing.

Like Watson, Ledet is also committed to keeping Kouri-Vini alive through zydeco (Credit: Stephen Saks Photography/Alamy)

“My goal is to become fluent enough to not only speak it, but to read and write it, so I can offer it to other people free of charge,” Ledet said. “It’s that important to keep it going, because it’s definitely a part of Louisiana.” His next album, Médikamen (Medication), is entirely in Kouri-Vini. He channels the late Clifton Chenier, the “King of Zydeco”, who made several recordings in the language.

“Music is my medication,” Ledet said. “Whenever I’m feeling down, it picks me up. When people hear zydeco, it doesn’t matter what’s going on in their life; it puts a smile on their face.” He hopes it will also put a few Kouri-Vini phrases on their tongue.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly attributed a quote to US President Theodore Roosevelt.

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.