World Bank calls for debt relief as funds flee poor countries

The World Bank’s top economist called on private lenders to shoulder some of the cost of debt forgiveness for the poorest countries, as record high repayments drain budgets that should be focused on health, education and infrastructure.

Interest payments alone by the lowest-income nations ballooned to a record $34.6 billion in 2023, quadrupling over the past decade, the bank said in its latest International Debt Report. Including principal, those 78 nations are paying $96.2 billion annually to service $1.1 trillion in debt.

More alarming, according to Chief Economist Indermit Gill, is that private lenders have pulled almost $13 billion more in service payments from those countries than they injected in new financing over the last two years. That burden is diverting funds from urgently needed investments at home, in areas from public health to climate change.

The World Bank’s latest warning caps a period of growing strain on the finances of poor countries, after a pandemic that forced higher spending and then a worldwide surge in interest rates that raised debt costs. Countries including Sri Lanka and Zambia have defaulted since Covid hit, while others like Pakistan and Kenya teetered on the brink — and international efforts to agree on a wider fix, including relief from private loans too, kept hitting snags.

“It’s time to face the reality: the poorest countries facing debt distress need debt relief if they are to have a shot at lasting prosperity,” Gill wrote in the forward to the report released Tuesday. “Private creditors that make risky, high-interest loans to poor countries ought to bear a fair share of the cost when the bet goes bad.”

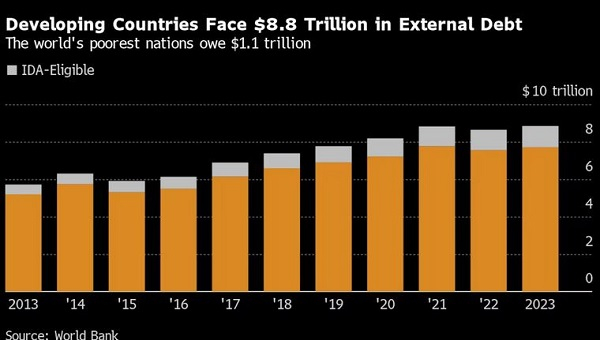

For all developing countries, including massive and stable economies such as China and India, total debt payments hit $1.4 trillion last year — including interest of $406 billion — on $8.8 trillion in debt. Over the past two years, that broader group has paid private investors $141 billion more than they’ve seen in new loans, according to the World Bank report.

“That reflects a broken financing system,” Gill wrote, adding that the idea hatched a decade ago that private capital could flood into poor countries to turbocharge development “proved to be a fantasy.”

Gill’s verdict comes as the bank’s president, Ajay Banga, has made one of his top priorities incentivizing more private capital to invest in development alongside multilateral lenders.

The bank is also working with its sister institution, the International Monetary Fund, to steer countries in debt distress toward policies that bolster their finances and lower borrowing costs.

Many nations accumulated debt piles by borrowing heavily in the pre-Covid years when interest rates were low — especially from China and private lenders, which have grown to be significant creditors to poor countries. Problems escalated when the pandemic pushed governments into emergency spending, and then interest rates rose to fight post-Covid inflation.

The consequences are still playing out. A report by credit rating firm S&P Global in October predicted that “sovereigns will default more frequently on foreign currency debt over the next 10 years than they did in the past.”

The flight of private capital from emerging markets has continued this year. Investors using hard currencies such as dollars or euros have pulled roughly $13.6 billion from emerging-market debt funds in 2024, after withdrawing almost $23 billion the previous year, according to data from Bank of America.

The biggest risks are concentrated among the 78 poorest countries categorized by the World Bank as eligible to receive low- or no-interest financing and grants from its International Development Association fund.

Many of those countries face “a metastasizing solvency crisis that continues to be misdiagnosed as a liquidity problem,” Gill wrote.

Source: bloomberg.com