Exporting Hazard: The dark side of European used cars and spare-parts trade in Ghana

• UN Comtrade data show that the European Union exported over US$275million worth of vehicles to Ghana in the last five years. “Many of these vehicles are comparable to those we consider end-of-life vehicles”.

• With an estimated 40% of Accra’s air pollution concentrations related to vehicle transport emissions, Accra’s yearly concentration of air pollution was 11 times higher than the WHO air quality standard as of 2020.

• Ghana’s local regulators, the Ghana Road Safety Authority and Ghana Standards Authority, do not currently have any scientific specifications and emissions standards for auto spare-parts exported to the country.

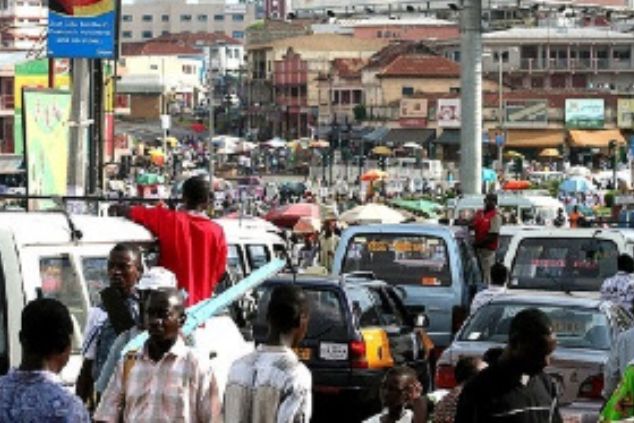

In the bustling market of Abossey Okai in Accra, Ghana, one will find a vast array of imported auto parts from Europe and other parts of the world. The market is known for its wide variety of auto spare-parts, including both new and used parts, and is a popular destination for those looking to repair or upgrade their vehicles.

However, the importation of end-of-life vehicles and used auto parts from Europe to the market is not only putting lives at risk but also contributing to significant environmental pollution in Ghana.

Robert Dumevo, a mechanic who runs his shop at Lapaz – a suburb of Accra, recounts how he narrowly escaped death on the N1 motorway in Accra. He had replaced a broken exhaust pipe on a client’s Hyundai Sonata, unaware that the replaced part was also faulty – and it in the vehicle catching fire during a test-drive.

“I was driving a ticking time-bomb. My lungs were engulfed in smoke and I struggled to breathe. I realised there was trouble when I tried to escape and my seat belt got jammed. I could feel the fire under my feet,” Robert recalled with some hint of trepidation.

Photo credit: Used spare parts shops at Abossey Okai, Accra, 2022, Ghana. Daniel Abugre Anyorigya

Robert blames “unscrupulous spare-part dealers” at Abossey Okai – Accra’s largest hub of spare-parts importers where he bought the replacement part. “When you buy a used spare-part at Abossey Okai you cannot tell if it is fake, sub-standard or faulty. Some businessmen are involved in the selling of sub-standard spare-parts, making it difficult to do our work,” he explained.

Abossey Okai – A morgue for used car parts and end-of-life (ELVs) vehicles from Europe

Clement Boateng the chairman of the Abossey Okai Spare Parts Dealers Association, admitted that the prevalence of sub-standard auto parts ending up in vehicles and causing safety and environmental issues stems from the nature of auto parts imported from abroad. “Most of the second-hand auto parts dealers import parts from salvaged and end-of-life vehicles,” Clement revealed.

There are “over 15,000 shops” at Abossey Okai, with over fifty-five percent engaged in the import of used auto spare-parts from abroad, he said, adding: “When importing used auto parts, you must be there for physical inspection or have a trusted client. Otherwise, you stay in Ghana and they will load trash auto parts into containers to you”.

The used automobile parts and vehicle industry is one of the biggest in Europe and West Africa. Data provided by the Dutch Environment and Transport Inspectorate (ILT), show that “Europe exports over a million light-duty vehicles” to Africa annually. UN Comtrade data show that the European Union has exported over US$275million worth of vehicles to Ghana in the last five years, with Germany being the biggest exporter.

“Many of these vehicles are comparable to those we consider end-of-life vehicles,” ILT notes, bringing into question the nature of port inspections that take place in Europe before export.

Frank Duru is a car exporter with several years of experience based in Germany. He explained that there are instances when an official car inspection before export is replaced by a personal glance of approval. “A few of them [vehicles] do not have the roadworthiness certificate, but we see they are in good condition,” he disclosed.

“Neither the exporting nor importing countries have minimum requirements in place to ensure that only quality used vehicles are traded,” said Veronica Ruiz Stannah, an expert on transportation at the United Nations Environment Programme.

This allows for a lot of used cars and car parts in poor condition to pass inspections at European harbours and depart for West Africa, where they create substantial safety, environmental and health problems for people like Robert.

Response to trade of ELVs and used spare-parts in Europe and Ghana

In 2020, ILT conducted a study on the European export of used vehicles to West Africa. The study revealed that 80 percent of 280,000 vehicles exported to West Africa from the Netherlands were “old and below the Euro 4/IV emission standard”, and often lacked requisite “roadworthiness certification”.

The study also noted that the trend was not entirely different among other European markets such as Germany, Belgium and France, Netherlands and Italy.

Marietta Harjono, a coordinating specialist at the Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate (ILT) of the Netherlands, explained that at the harbours inspectors can stop the “worst vehicles, when they are waste or hazardous waste,” after conducting checks with Customs officials.

Exhaust fumes from commercial vehicle in Accra, 2022. Credit Maxwell Ocloo

She however stressed that while a lot of the used cars may not be categorised as waste, they might still not be appropriate for export.

ILT in a 2021 proposal to the European Commission (EC) on the revision of EU regulation on end-of-life vehicles concluded that: “Environmental and health problems will arise in cases where third countries lack a proper system for handling vehicles that reach their end-of-life situation and become waste”.

The European Commission is currently in the process of revising its Directive on end-of-life vehicles (ELVs), but it remains uncertain if a “cross-border aspect” will be included in the final regulation to end the export of ELVs to places like Ghana and Nigeria according to the ILT.

The EC did not respond to questions about ELVs and used spare-parts ending up in places like Ghana.

Despite the health and environmental problems caused by end-of-life automobile parts and vehicles from Europe, Ghana’s local regulators – the Ghana Road Safety Authority and Ghana Standards Authority – do not currently have any scientific specifications and emissions standards for auto spare-parts exported to the country.

Head of Regulation, Inspection and Compliance at the Ghana Road Safety Authority, Kwame Koduah , told iWatch Africa that his Authority and the Ghana Standards Authority (GSA) are engaged in a conversation “to ensure that spare-parts imports at least meet some conformity test and standards”.

The Ghana Standards Authority in a written response as part of this investigation also noted that: “The GSA does not have a written policy specific to vehicle spare-parts. The Authority is currently pursuing the development of national standards for replacement parts (spare-parts)”.

Meanwhile, in 2002 Ghana introduced a regulation that made the import of vehicles over ten years more costly by imposing penalties.

Emissions, Health and Environmental Problems

In spite of this regulation, it is typical to encounter many cars releasing thick exhaust fumes while driving through Ghana’s capital, Accra – a health hazard for many pedestrians, street hawkers and shop owners resulting in thousands of deaths annually.

Accra’s air pollution is considered critical as around 16 percent of the air is severely polluted and unhealthy, with an additional 30 percent unhealthy for sensitive groups such as people with asthma, according to the Air Quality Index.

At an event to mark the International Day of Clean Air Blue Skies last September, Dr. Francis Chisaka Kasolo – the World Health Organisation Representative to Ghana, noted that air pollution was the biggest environmental risk responsible for premature deaths from heart-attacks, strokes and respiratory diseases in the country.

With an estimated 40 percent of Accra’s air pollution concentrations related to vehicle transport emissions, its yearly concentration of air pollution was 11 times higher than the WHO air quality standard as of 2020.

The country imports about 100,000 vehicles per year, 90 percent of which are used vehicles. Most of the cars currently used in Ghana are Euro 1 and 2, meaning that they are the most polluting according to the EU emission standards.

So far, officials in Ghana have failed to implement legislation passed in 2020 that aims to completely ban the import of vehicles older than 10 years.

Daniel Essel, Deputy Director at the Ministry of Transport in Ghana, during a session at COP27 praised the legislation but failed to mention that government had chosen not to implement it: raising issues about the commitment of Ghanaian officials to addressing concerns related to ELVs and used car parts.

“Policymakers in Ghana are not doing enough to curtail used vehicle consumption, and to that end reduce the harm – crashes, pollution, etc. – that come with it,” says Festival Godwin Boateng, a Ph.D. researcher at the Centre for Sustainable Urban Development at Columbia Climate School in New York.

Way Forward

To safeguard the environment and public safety, Dr. Boateng insists that any ban on ELVs in Ghana should be couched as part of broader policies: such as investments to make public transport, walking and cycling cleaner, safer and affordable, as well as investments in city planning and mini-bus electrification.

For a regional solution, the ILT recommends that: “African governments must agree as much as possible to harmonised or regional import standards for used vehicles. Whether it is on maximum age, minimum euro class, maximum mileage, proof of roadworthiness, and/or condition of the vehicles at export”.

Robert narrowly avoided a fatal outcome but, unfortunately, thousands – including the environment – bear the consequences from years of ineffective policies on the import of ELVs and used car parts.

Until the necessary actions are taken, Robert believes that “many people will continue to perish each year” through no fault of their own.

Additional reporting by Raluca Besliu, Daniel Abugre Anyorigya and Elfredah Kevin-Alerechi. This investigation was supported by Journalismfund.eu

Source: Gideon Sarpong, Contributor