Militant groups recruiting child fighters in Burkina Faso – Report

Child soldiers recruited by jihadists in Burkina Faso

Child soldiers recruited by jihadists in Burkina Faso

Awoken by gunshots in the middle of the night, residents of Solhan were shocked by who they saw among the attackers in the town in Burkina Faso’s Sahel region: children.

About 160 people were killed in June in the deadliest assault since the once peaceful West African nation was overrun by fighters linked to al-Qaida and the Islamic State about five years ago.

Witnesses of the Solhan attack said they saw children helping the fighters to burn down houses but did not see the minors killing anyone.

The government confirmed that children were involved in the assault.

As the violence increases, so too does the recruitment of child soldiers.

The number of children recruited by armed groups in Burkina Faso rose at least five-fold so far this year, up from four documented cases in all of last year, according to information seen by the AP in an unpublished report by international aid and conflict experts.

“As parents, we are really afraid. Children are more vulnerable to be recruited by jihadists because they are not conscious enough to decide (to make the right choice),” said Isma Heella, a Dori resident and father of a 4-year-old boy.

Aid groups are seeing more children with jihadi fighters at roadside checkpoints in the Sahel — an arid region that passes through Burkina Faso but stretches straight across the African continent just south of the Sahara.

In recent years, the western Sahel has become an epicentre of Islamist violence.

Civil society organizations also accuse army troops of contributing to the problem by committing abuses against civilians suspected of being militants.

The lack of access to education, health, and basic services contributes to making children more vulnerable.

“Those children have no access to a good education, minimum health care, minimum dignity. They are therefore vulnerable targets and easy to be recruited by extremist groups,” said Maimouna Ba, head of operations for Women for the Dignity of the Sahel, a Dori-based advocacy group.

“The army also commits abuses in front of them, and these actions contribute to traumatize them for life”, Ba added.

The army has denied these allegations, along with accusations that it was slow in responding to the attack in Solhan, but would not provide a detailed comment.

“We see children who are angry because they don’t understand what happened to their parents who were killed without explanation, without any form of justice,” said Ba.

As they get older, children may become angry and start asking why the state is not helping them, she said.

At least 14 boys are being held in the capital of Ouagadougou for alleged association with militant armed groups, according to Burkina Faso’s public prosecutor at the high court in the city.

The effects of the conflict on children — including their recruitment as soldiers, but also attacks on schools and children themselves — have become so concerning that this year Burkina Faso was added for the first time to the U.N.’s annual report on Children and Armed Conflict.

During a recent trip to Dori, a town in the region where nearly 1,200 people fled after the attack on Solhan, the AP spoke with eight survivors, five of whom said they either heard or saw children partake in the violence.

Burkina Faso’s ill-equipped and under-trained army is struggling to stem the violence, which has killed thousands and displaced 1.3 million people since the jihadi attacks began.

Experts on child recruitment say that poverty pushes some children toward armed groups.

The deteriorating security is sparking unrest, with protests across the country demanding the government take stronger action.

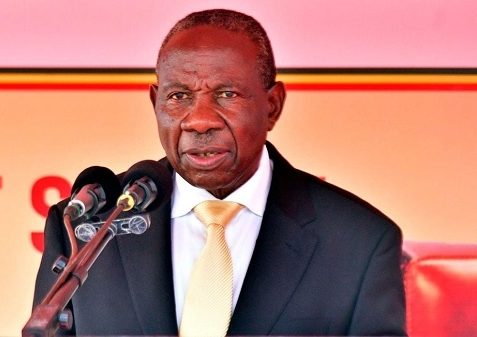

In response, President Roch Marc Christian Kabore fired his security and defence ministers, appointing himself minister of defence.

The government has not yet signed an agreement with the United Nations that would help it to treat such children as victims, not perpetrators, for instance, by moving them from prison to centres where they could receive psychological care.

Preventing further recruitment, meanwhile, means tackling economic hardship and all that comes with it, including helping children who have left school to catch up on their lessons.

For now, many parents, already struggling to feed, clothe and educate their children, feel powerless to protect them.